Warm the heel. Wipe with pad. Prick the skin. Massage the foot.

Squeeze one drop — only one drop.

Fill all five circles on the page with blood.

After collecting the sample, nurses send the newborn screening form to be tested for up to 100 different targeted disorders, including phenylketonuria, an inherited disease that can cause permanent intellectual disability when not diagnosed early in life.

Neonatal screening is just one application of the triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, which was pioneered by Chris Enke, a professor at Michigan State University, and his graduate student at the time, Richard Yost. Yost, now a chemistry professor at the University of Florida, will be inducted Sept. 20 into the Florida Inventors Hall of Fame for his work on the mass spectrometer that revolutionized the field.

WHAT IS IT?

A spectrometer is a device that is used to separate and identify the components of mixtures and the structure of molecules. Mass spectrometers do that by breaking molecules into ions and filtering those ions according to their mass.

The ions are accelerated with an electric field through a device with four parallel metal rods called a quadrupole. The filtering quadrupole allows only ions with a certain mass to pass through it. This way, scientists can get an idea of which ions are present in the compound.

However, there are multiple compounds that have the same mass. In order to fully separate and identify their samples, Yost and Enke wanted a more sophisticated method of chemical analysis.

As a first-year graduate student at Michigan State University, Yost thought he’d use two of these devices back-to-back: a tandem quadrupole.

HOW IT HAPPENED

Enke and Yost quickly transformed from mentor-mentee to partners on the project. “We were collaborators,” Enke said over the phone. “Discovering together.”

The team wrote and submitted a grant proposal to the National Science Foundation.

“I was pretty bold for a first-year grad student,” Yost said. “I even referred to the device in the grant as ‘the ultimate system for chemical analysis.’”

But the grant proposal was rejected. Hard.

The reviewers commented that Yost’s idea was stupid and would never work. “The quadrupole isn’t a real mass spectrometer — it’s just a toy,” they said.

Unfazed, Yost submitted a copy of the proposal to the Office of Naval Research, which was much more receptive to the idea. The Navy offered Yost and Enke money and around 2,000 pounds of stainless steel to make it happen.

Yost and Enke ran into some unexpected help along the way when they discovered that Jim Morrison, a researcher in Australia, had already created a device that was very similar to the one they had proposed, but for a very different purpose. Morrison’s device, however, was having some difficulties.

The Navy paid for Yost to travel to Australia and use Morrison’s equipment to figure out why the device was not working. In Morrison’s lab, they uncovered the hidden hurdle, known as low-energy fragmentation, which has been used in every mass spectrometer made since then, according to Enke.

“It turns out that what we wanted to do — fragment the ions by collision in the center quadrupole — was the thing that got in the way of making the measurements that he wanted to make,” Yost said. “What to us was our signal was to him background interference.”

Yost returned to Michigan State with Enke and used what he had learned from Morrison’s lab to update their device. The fragmentation that was getting in the way of Morrison’s results was the one step Yost and Enke had been missing.

They added a third quadrupole in the center, and it worked. Hence, the triple quadrupole mass spectrometer was born.

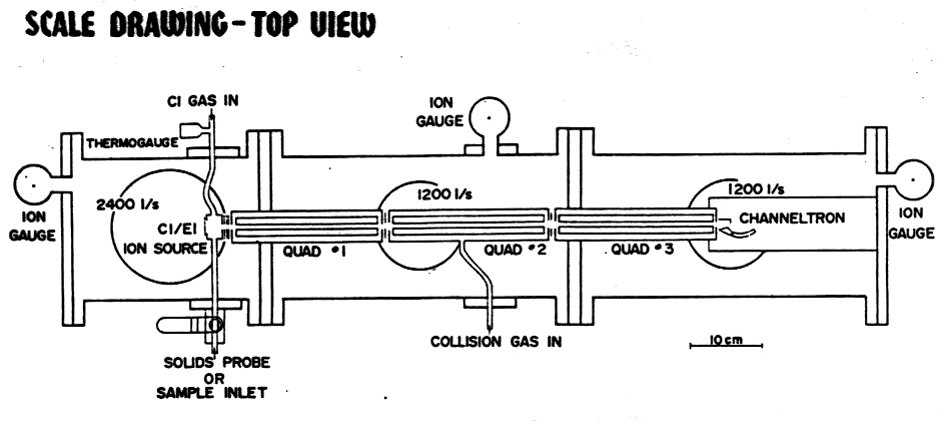

Yost's blueprints for the original device

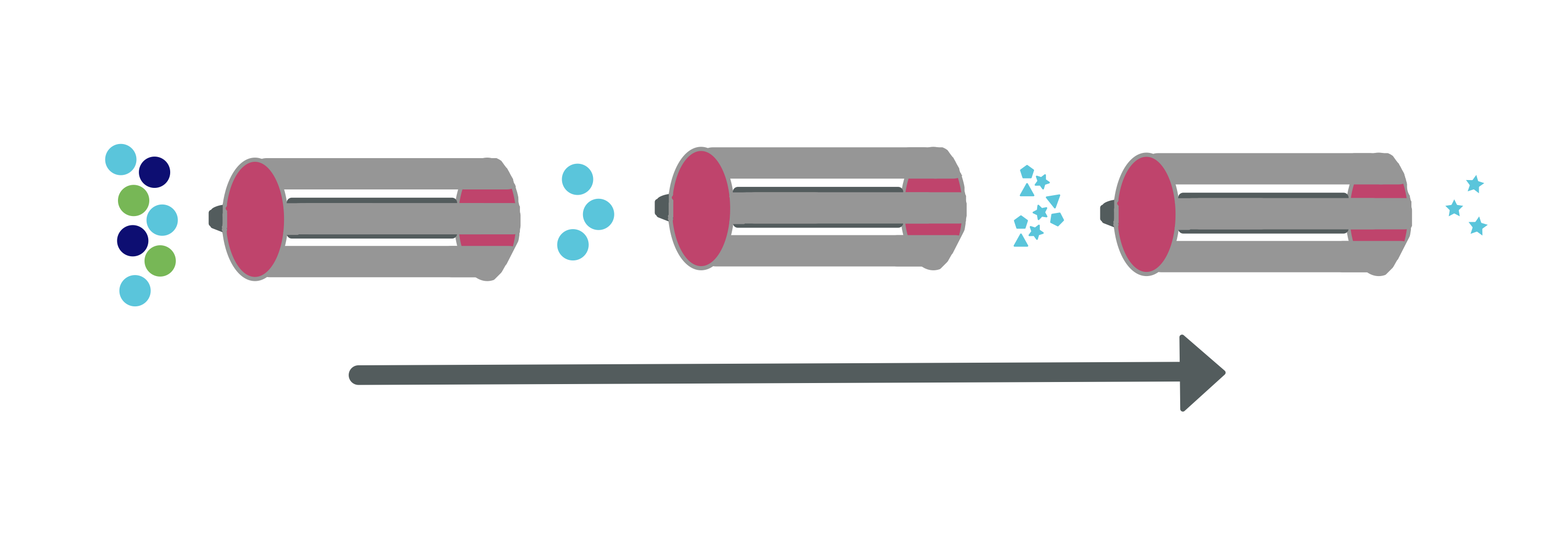

The first quadrupole filters ions by mass. The second one breaks, or fragments, the ions into smaller masses and the third one filters them again based on the new masses. By filtering twice, they are able to effectively separate and identify the substance. Before Yost left graduate school, they had applied for a patent on the device.

A simplified sketch of the process of triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Illustration by Zack Savitsky.

SO WHAT?

"Now it’s the most common mass spec in the world, and it sells over $1 billion a year, which is fairly mind-boggling for something that was a stupid idea that was never going to work," Yost said.

While Yost and Enke received only a “modest” 5 percent share of royalties until the patent expired, they had a non-exclusive license, and over the past 40 years companies and individuals have used the device in hospitals, environmental projects, pharmaceutical testing and beyond.

It also helps catch diseases like PKU before it's too late.

“They now test about 10 million babies around the world each year, and this instrument is the only way you can really do it,” Yost said. “We probably save 10,000 babies from early death. It’s certainly the application that makes my wife the proudest.”

Photos courtesy of Richard Yost