How Mary McLeod Bethune became the first Black woman selected to represent a state at the U.S. Capitol

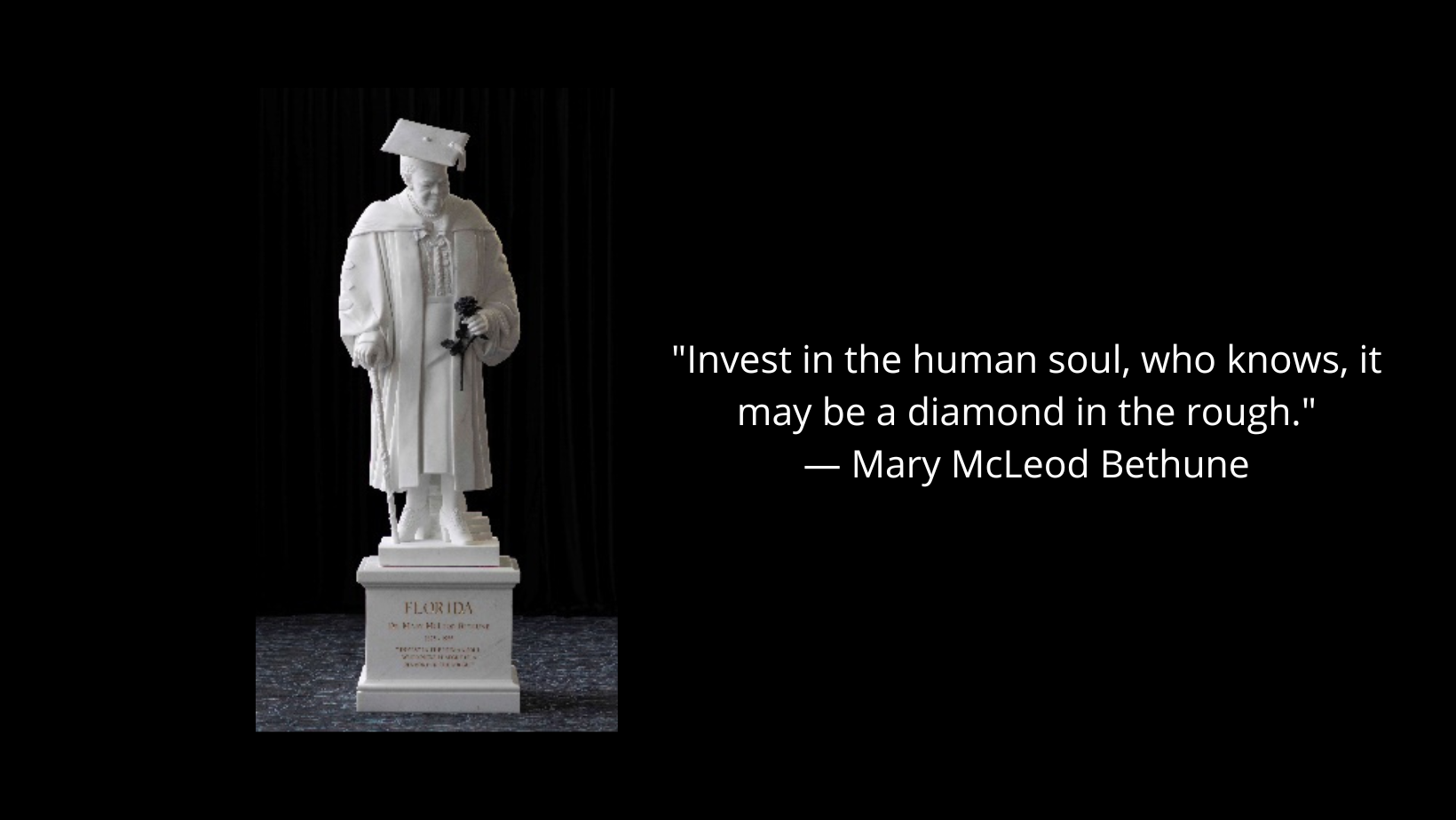

Mary McLeod Bethune statue

Welcome to From Florida, a podcast that showcases the student success, teaching excellence and groundbreaking research taking place at the University of Florida.

Florida made history this summer with the installation of a statue of Mary McLeod Bethune in the National Statuary Hall collection, making her the first Black woman selected to represent a state at the U.S. Capitol. UF History Professor Paul Ortiz and Yolanda Cash Jackson, a member of the statue committee and a UF alumna, talk about Mary’s many accomplishments and her selection. Produced by Nicci Brown, Brooke Adams, Emma Richards and James L. Sullivan. Original music by Daniel Townsend, a doctoral candidate in music composition in the College of the Arts.

Nicci Brown: Each state selects two statues of distinguished citizens to represent it in the U.S. Capitol. This summer, Florida made history with the installation of a statue of Mary McLeod Bethune in National Statuary Hall. Who was Mary and why was she chosen to represent Florida?

I'm your host, Nicci Brown and today on From Florida, we're going to talk about Mary and the significant impact she had on our state, the nation and internationally. Our first guest is Paul Ortiz, a history professor and director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at UF. Paul participated in a new documentary on Mary McLeod Bethune and wrote about her in his first book, Emancipation Betrayed.

Paul, welcome.

Paul Ortiz: I'm so glad to be back. Thank you so much.

Nicci Brown: Paul, for those who may not know, who was Mary McLeod Bethune? Why is she an important historical figure?

Paul Ortiz: Mary McLeod Bethune was the founder, in 1904, of the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls. Our listeners may know this school now as Bethune-Cookman University, but she founded the school in 1904 during the least promising moment to found an educational institution for African Americans in Florida. The state educational outlays for African American students were sometimes a fifth of those compared vis-a-vis to their white counterparts. 1904 was the high tide of lynching in Florida.

Because of her advocacy of equal education and her belief in democracy, Dr. Bethune was also frequently targeted by the Ku Klux Klan. She had people around her, most of her entire life, to just protect her and defend her physically from harm. She came to prominence, really, as an educational advocate but also as a political organizer. She was very active in the women's suffrage movement.

Dr. Bethune was always way ahead of her time. She believes in women's equality long before that's a thing to believe in. She believes in women's right to vote. She believes in racial equality. She believes that all nations, in fact, should be equal, and so she plays a big part in the writing of the UN charter in San Francisco after World War II. It's so fitting that we're able to finally honor her with a statue in the nation's Capitol.

Paul Ortiz is a history professor and director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. Photo credit: Paul Ortiz

Nicci Brown: It seems like she was an educator in more than one sense of the word, educating both within the school walls but also to the public in general. Can you tell us a little bit more about her influence on the Florida education system specifically?

Paul Ortiz: She was very successful in fundraising, not only for Daytona Normal, her school, but also for other Black educational institutions across the state, including K-12 public schools. Again, remember that the state of Florida is not parsing out tax dollars in an equitable manner for Black education. Dr. Bethune is actually going out and doing things like bake sales, raising money, raising funds to support and to improve Black education all throughout the state. That's one of the reasons I think she's so popular and just such a beloved figure, because people see her as not only an educational expert, the founder of a college, but also someone who cares about my children, wants my children to have an equal opportunity in the society. Again, in 1904, that's an extraordinary stance to take.

Part of the key to understanding her influence was how she connected her organizing work with her education work. She was a founder and a leader of the Southeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs. She was the head of the Florida Federation of Colored Women's Clubs. This was a network of Black women, many of whom were educators, actually.

Nicci Brown: It seems like she was very ingrained within the community as well. She wasn't just this person who was a thinker; she was a doer.

Paul Ortiz: Exactly. She gains this reputation fairly rapidly and becomes an adviser, kind of impromptu or unofficial, but very important advisor to Franklin Roosevelt, to Harry Truman. She befriends Eleanor Roosevelt, of course, Franklin Roosevelt's wife. Eleanor Roosevelt is this incredible international political figure in her own right. Mrs. Roosevelt and Dr. Bethune strike up this really extraordinary relationship in terms of Dr. Bethune becomes one of Eleanor Roosevelt's main sounding boards. "Well, how can we improve the society? How can we make it more equitable? What do we do about the crisis of farming in the South? How do we challenge this issue of one-party rule in states like Florida?"

Dr. Bethune is one of those people who is a do-it person. She's what I would call a step-up-to-the-plate kind of person and she never lets people off the hook. People will tell her in 1920, "Dr. Bethune, you're asking me to try to register to vote, to pay my poll taxes in Florida, with the Klan raging across the state. This is so dangerous. How can you ask me to do that?" She's like, "Well, I'm going to do it, so I expect you to do I,t too. If you care about your children's education, if you care about the health of your community, if you care about fighting corruption in the state, by heavens, you're going to go and pay your poll tax, and you're going to try to vote."

This is such an astonishing thing. The more I look into to Dr. Bethune, the more I really believe she's really one of the most remarkable Americans of the 20th Century, if not of all U.S. history. It isn't just that she asks Black Floridians to try to vote in a state with the highest lynching rate per capita, on Election Day, she goes to the polls and she walks up and down the line. She'll make lemonade or have her students make lemonade, bolster people's spirits, "Hey, stay in the line. Don't worry about those white people yelling across the street and threatening you physically. We're going to handle that. We've got to stay in this line if we care about the future of our community."

Nicci Brown: Speaking of communities, what kind of impact did she have on the white community as well? Did she make inroads and have people really follow her in those circles as well?

Paul Ortiz: Let's think of the international and the national first, then we can move back to the statewide. I mentioned earlier that Dr. Bethune ends up going to what becomes the founding meeting of the United Nations and Harry Truman asks her to go for a very specific reason. One is she has all this gravitas. She has a large following. She's really highly respected by education and political leaders nationwide. In fact, she probably has a greater respect outside of Florida among white leaders than she does in Florida.

In Florida, frankly, she is a thorn in the side of white rule because she is demolishing all of the excuses that there were for white rule. One-party rule in Florida was based on the notion of Black inferiority. Well, Dr. Bethune didn't believe in Black inferiority. The Jim Crow system was based upon Black people sit here in the back, white people sit in the front, everything separate. Dr. Bethune never believed in that.

When white individuals would come to visit Daytona Normal and many of them came to visit because she was a great choir instructor. The girls in the school were nationwide famous for their singing, for their choirs, for their bands, et cetera, so a lot of people would come to campus for Christmas programs, for holiday programs.

One of the things her former students — I'm just so lucky because I'm just old enough to have interviewed some of her former students, who, in the '90s, were quite old — but they remembered her very vividly. The thing that impressed them the most, really, were two things. One was Dr. Bethune insisted that all white visitors to Daytona Normal in 1904 not segregate themselves. She said, "If you want to come onto my school's campus, you will sit where there is a seat. You will not sit in the front. You will not sit in the back. You'll sit where there's an opening."

She would often use this phrase, "This is a democracy working in the South." To me, that's maybe the most important phrase if you want to think about who Dr. Bethune was. Saying "this is a democracy working in the South" in 1904 is a pretty heady thing because, again, Florida is a one-party state. Very few African Americans have the ability to vote.

The other thing that really stands out, and again, this is something that we learned from interviewing former students of Dr. Bethune, is the demand she made on her female students, who she called girls, as they became young women, the demand she made in the entire society, that Black womanhood would be respected, must be respected.

Dr. Bethune insisted that Black women were the key to the advancement of the entire race and, ultimately, the entire state and ultimately the entire country. She really made a big impact on people because this idea that Black women, in particular, should be seen as equal to white women in 1904 was quite an astonishing breakthrough. It wasn't something that you often heard people say.

Nicci Brown: She sounds like an incredibly brave individual. What were some of the other causes that she advocated for?

Paul Ortiz: Dr. Bethune, for many years, was the vice president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or the NAACP. In that capacity, she campaigned against lynching. She campaigned against debt peonage.

The debt peonage campaign was a very interesting campaign. I've had the opportunity to look at some of Dr. Bethune's papers and one of the things that's so moving is, when you're reading her papers and the files and the letters that people sent her, and they sent hundreds and thousands of letters, Black people and even white people, who were in difficult situations would write to her and would say, "We just want to let you know that there's 10 of us working at a migrant labor camp near Lake Okeechobee. Our employer won't let us leave. We're literally held captive as if we're slaves. Can you help?" Then when you follow that correspondence up, Dr. Bethune is writing the Justice Department to say, "Hey, there's a problem here down at Lake Okeechobee." Now, remember, this is the 1920s and '30s. This is a time when debt peonage and really terrible labor violence is happening all over the South and, in fact, all over the country.

I think this is another one of the reasons why Dr. Bethune is such a popular person. She isn't just about the middle class. She isn't just about, "Oh, I know Eleanor Roosevelt" or "I know Harry Truman." She always stayed true to her roots. She was such a beloved figure that, again, when I would interview people who had been her students, they would just begin weeping in the middle of the interview. They would think about the impact that she had on them as young women and then their careers and just this incredible respect that they had for her because she respected them.

Nicci Brown: In being ahead of her time, she's still having an impact, it sounds like, on many, many people, and also on our state and nation. Paul, thank you so much for giving us some insights on this remarkable person.

Paul Ortiz: Thank you.

Nicci Brown: Now I'm delighted to have Yolanda Cash Jackson join us. Yolanda is a UF alumna, a Double Gator, in fact, which means she has two University of Florida degrees. She is a shareholder with the Becker Law Firm and is a lobbyist for Bethune-Cookman University. She joined the statue project in 2016 and was in Washington, D.C., for the unveiling in Statuary Hall. What a moment that must have been!

Welcome, Yolanda.

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Thank you. It was a moment!

Nicci Brown: Can you tell us about the start of the journey to create the Mary McLeod Bethune statue and where did that idea actually come from?

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Well, I think you have to say that it's the culmination of a number of people that decided after, in 2016, when there was a decision to remove the Confederate General Kirby Smith from Statuary Hall representing Florida, and alumni, staff, friends of Daytona, friends of Mary McLeod Bethune decided that perhaps they should throw her name in the ring to be nominated as the replacement.

Nicci Brown: Can you tell us a little bit more about the lobbying and fundraising efforts that helped make this statue a reality? It seems like it was just a huge effort by a number of people.

Yolanda Cash Jackson: It was a huge effort by a number of people, starting with the university. The university was very active from the beginning in getting students, alumni, friends of the university involved in the effort. Then, certainly, the business leaders of Volusia County, of Daytona Beach, people like Nancy Lohman, people like the folks from Brown & Brown, just community leaders, decided that they would get together and make sure to make this a reality. The then-president of Bethune-Cookman University also made a commitment to help raise the funds. There needed to be funds for the sculptor and that was a whole other selection process as to selecting Nilda Comas as the sculptor.

Yolanda Cash Jackson is a UF alumna, a shareholder with the Becker & Poliakoff law firm and a lobbyist for Bethune-Cookman University. Photo credit: Yolanda Cash Jackson

Nicci Brown: It sounds like we're not talking about hundreds, we're talking about thousands of people who had a role in making this a reality.

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Yes, if you could figure that this was going to be a first. I don't think when we started this journey that the impact of what was going to be -- those of us who were on the working lines -- the impact was certainly beyond our imagination, to think that the first African American to be named for a state in Statuary Hall would be Mary McLeod Bethune.

Nicci Brown: Can you walk us through some of those steps. This is not a simple, quick vote process or anything like that. There are a number of things that you went through to make this happen. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Once the statue was removed, then there was legislation filed by Representative Patrick Henry, then-Representative Henry, Senator Perry Thurston. He did it twice, actually. Quiet as this was kept the first year, the bill did not get through the process. But the second year, the bill did get through the process and there was a proud cosponsor also, Representative Leek, so it was bipartisan, basically, Republicans and Democrats in the House that made sure the bill got over the threshold.

And in fact, on the day that the bill passed, the Bethune-Cookman University choir performed, and that was quite an amazing day, the day of that performance and the day that the bill actually passed.

Then, of course, we had to have the governor to sign the bill, and that took some time. Then even after the governor signed the bill, we then had a new governor that came in. Rick Scott went out. Ron DeSantis came in. It was Governor DeSantis that went ahead with the process of getting it approved in Washington and get it signed off in Washington. We also had a change of presidents during that time, so there was a little delay there.

Nicci Brown: And you mentioned the choir. I understand through earlier conversations that the choir was particularly important to Dr. Bethune.

Yolanda Cash Jackson: The choir was particularly important. Her students were particularly important.

One part that I did skip, and that is that there was an unveiling in Italy and I was able to go to that. The choir did not attend as a whole, but some of those students who sang in the first choir that presented when the bill was passed in Tallahassee were also on the unveiling program there in Italy.

The students at Bethune-Cookman were her life, were what she called her “black roses.” That's why she is symbolically holding a black rose. The students were the reason for her being, and that was depicted in the statue in the way that Nilda presented the statue.

Nicci Brown: Can you tell us a little bit more about some of those other symbolic elements that are captured with the statue itself and also its place now in our nation's capital?

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Well, I am hardly the expert on symbolism, except for those things that stand out for me. The things that stand out to me and have stood out to others is the symbolism of her robe depicting education, her cane, she did have a cane, that indicated some type of sternness, some kind of steadiness. That was certainly symbolic to me.

The last will and testament is very, very important in the story of Mary McLeod Bethune. That is symbolized in the base of the statue with the books that have representations of that. And certainly, the black rose which is being held. Even the marble that was selected is the marble that came out of the quarry of Michelangelo, and so even that. And her eyes. Some people say that her eyes follow you, as if you are following the progress of the students, I've heard some people say. Just an amazing job that Nilda did to create the likeness of Mary McLeod Bethune and capture her sternness, her strength and her life's work.

Nicci Brown: I'm going to ask you to, I guess, project again, but do you think that she ever would've thought this would've happened, that she would be represented in the nation's capitol?

Yolanda Cash Jackson: From everything that I've learned about Ms. Bethune, she was certainly humble. This was a woman who was way ahead of her time, when women were not counseling presidents and she was, particularly women of color, particularly Black women. I think that she would not be surprised of her success because she was one who strove for the very, very best.

I think it was surprising maybe to us that the state of Florida would recognize her, but I tell you, it was such a wonderful bringing together of love and respect for Mary McLeod Bethune to make sure that she was in Statuary Hall. There were some other folks that were finalists as well, but the work of the students, the work of alumni, the work of friends made sure that it happened.

Nicci Brown: I can tell that it obviously meant a lot to you as well.

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Yeah, it did. As a lobbyist, sometimes you work on projects people never know that you are working on, sometimes very, very significant things. That's just not the role of a lobbyist. You are an advocate and sometimes you advocate in silence. The ability to join in in such a historic time is a lobbyist's dream.

We had a team of people I have to mention. The other folks at Becker & Poliakoff, some who have left the firm before this actually passed, Mario Bailey, Karen Skyers and others, they were all a part of this as well. It's an exciting time for a lobbyist. We don't get a chance to be out on the forefront that often.

Nicci Brown: Was it emotional?

Yolanda Cash Jackson: I think the most emotion, actually, was the day that the bill passed, because to have those students to sing was very emotional.

The other emotional time was in the studio where we actually saw the statue for the first time, without the base and the gold letters. The folks who had gone with us to Italy, some students, the then-president of Bethune University, Hiram Powell, and one of the former deans, Dean Henry, sang the school song. That was a very emotional time. It was impromptu but so impactful.

Nicci Brown: Yolanda, congratulations on the role that you played in this, and to everyone who played a part in it. Thank you so very much for joining us today.

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Well, thank you for recognizing Dr. Bethune. We also have a bronze statue that's coming to Daytona in August, the end of August, and so we're looking forward to seeing that. That will remain in Daytona.

Nicci Brown: Sounds wonderful. Thank you.

Yolanda Cash Jackson: Thank you.

Nicci Brown: Listeners, thank you for joining us. Our executive producer is Brooke Adams, our technical producer is James Sullivan, and our editorial assistant is Emma Richards. I hope you'll tune in next week.