With lasers, smoke and a wind tunnel, UF helps federal agency investigate deadly Hurricane Maria

As Floridians brace for hurricanes amid the wild weather of 2025, some University of Florida researchers have their eyes on 2017’s Hurricane Maria, the deadly Category 4 storm that pummeled Puerto Rico.

Engineering professor and natural hazards researcher Brian Phillips, Ph.D., is leading UF’s efforts in a Hurricane Maria investigation conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, known as NIST.

The goal is increased safety and resilience amid deadly conditions.

Maria killed nearly 3,000 people and caused more than $90 billion in damage. Most of the island’s wind sensors and weather stations failed as the storm raged, leaving responders and investigators with few reliable weather measurements.

What went wrong?

Phillips and UF storm researchers are helping answer that question — and provide safety and structural recommendations — as part of NIST’s Hurricane Maria investigation. The full report will be released in 2026, but NIST recently published preliminary findings; some of the hazard and structural load data was derived from wind tunnel tests at UF's NHERI Experimental Facility in the Powell Family Structure and Materials Laboratory on UF’s East Campus in Gainesville.

“Our wind tunnel has a strong reputation in the wind-engineering community for its unique flow control and measurement capabilities We worked with NIST to develop a test campaign to study the wind conditions Puerto Rico’s mountainous terrain and the resulting loads of critical infrastructure,” said Phillips, a civil and coastal engineering professor with UF’s Engineering School of Sustainable Infrastructure & Environment.

“UF,” he added, “has one of the premier research wind tunnels in the country and it enables us to pursue impactful research like this.”

As part of the NIST investigation, Phillips and his team created 1-to-3100 scale topographic models of regions in Puerto Rico — about 12 kilometers shrunk down to four meters, Phillips said. They set up those models in the wind tunnel and replicated wind flow over the topography.

“These initial tests were designed to understand the influence of the complex topography had on the wind,” Phillips said. Flow was measured using velocity probes and particle image velocimetry (PIV).

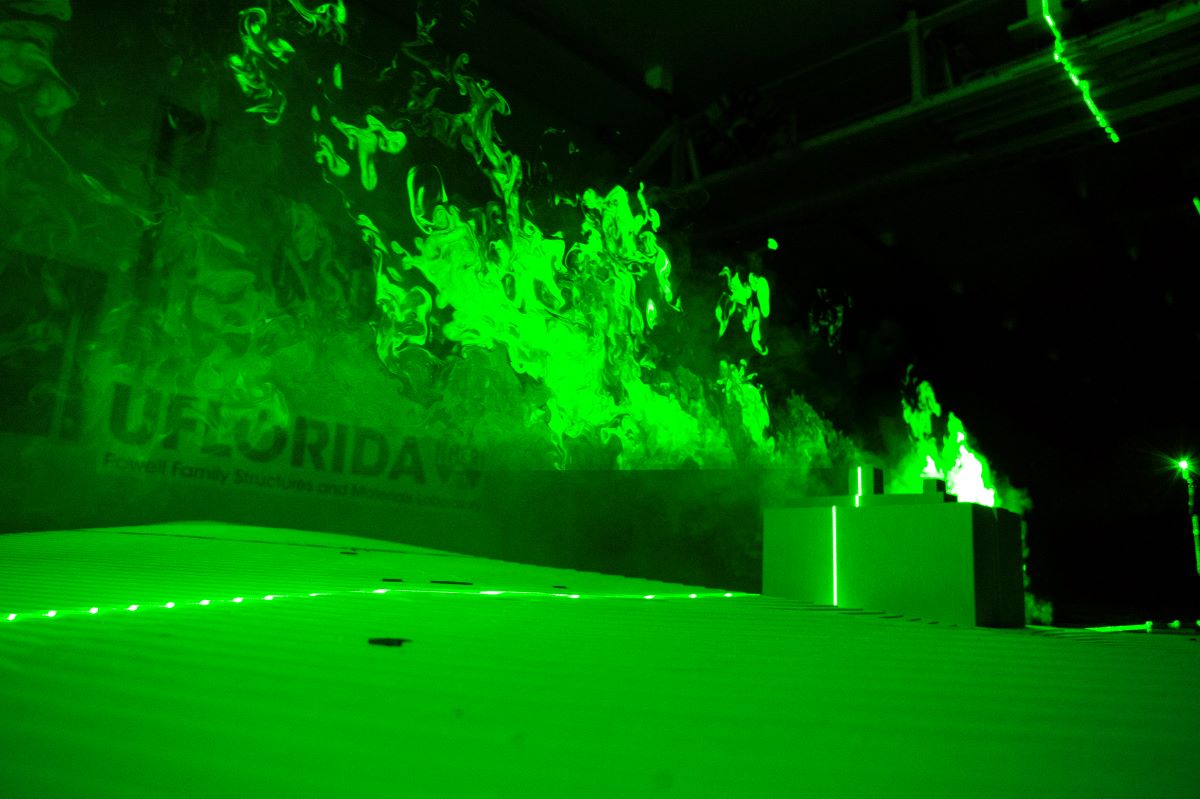

These topographic model tests were followed by 1-to-100 scale tests on models of two hospitals in Puerto Rico. In addition to surface pressure measurements, the team conducted qualitative flow visualization tests using smoke, lasers, and high-speed cameras.

“The capabilities of the UF wind tunnel enabled us to investigate the hurricane winds at two different scales,” said NIST’s lead Hurricane Maria investigator, Joseph Main, “so we could measure how the winds were accelerated by Puerto Rico’s mountainous topography and then how those winds translated into loads on critical buildings.”

Maria’s flooding blocked roads to hospitals and shelters. The hospitals themselves were heavily damaged by the storm, NIST reported. Reduced access to healthcare was a major factor in the death toll.

“It's good to take a step back,” Phillips said about the overall investigation. “Researchers are approaching the disaster from multiple angles, including the better understanding of the hazard, the performance of critical infrastructure, public response and recovery.

“This holistic approach is needed to capture the complete picture and maximize what we can learn from the event. UF's primary contribution was understanding the hurricane wind field and the resulting structural loads, which is a critical piece of that puzzle.”

In finding infrastructure vulnerabilities, researchers contend the goal is integrating their findings into design standards for Puerto Rico’s unique topography and building codes. The findings also could be valuable to other storm-prone regions with complex topography.

NIST launched the investigation in 2018, noting Hurricane Maria “set off a cascade of building and infrastructure failures across Puerto Rico that had lasting impacts on society, including health care, business and education.”

“Our goal is to learn from that event to recommend improvements to building codes, standards and practices that will make communities more resilient to hurricanes and other hazards, not just in Puerto Rico but across the United States,” Main said.

The complete report is scheduled to be released in 2026, and NIST noted some findings may change before its release. But in July, NIST released some preliminary findings. They include:

- Peak wind speeds over flat terrain reached 140 mph. They accelerated to over 200 mph in some areas due to the steep hills and mountains. The mountains also intensified the rainfall, which reached 30 inches in some areas.

- Only three out of 22 weather stations were fully functional during the hurricane.

- 95.3% of schools on the island lost power for an average of over 100 days.

- “One important preliminary finding from the study is that emergency preparations work,” NIST reported.

“Businesses, schools and hospitals that took specific measures to prepare before Hurricane Maria were able to resume operations more quickly” said Maria Dillard, NIST’s associate lead Hurricane Maria investigator. Preparations included pre-established emergency plans, designated risk mitigation funds and backup power sources.