A year after liftoff: UF scientist reflects on historic space flight and the future of biology beyond Earth

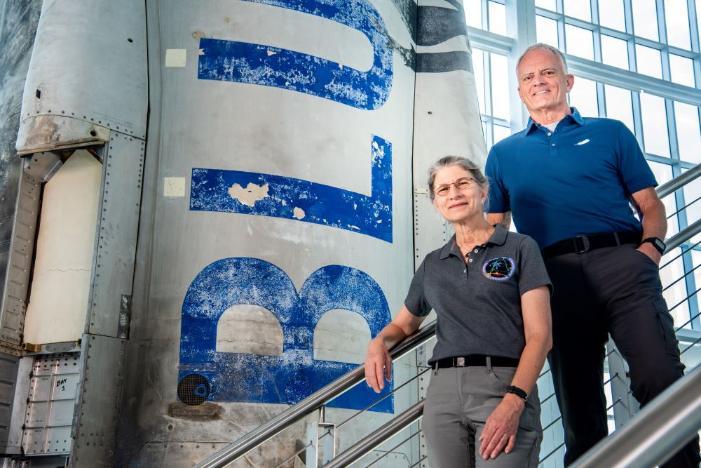

One year after his pioneering flight aboard Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket, University of Florida space biologist Rob Ferl, Ph.D., is still processing what it meant — not just for his career, but for science itself.

“What stands out the most is just the overwhelming gratitude,” Ferl said. “It was such an amazing opportunity for a scientist to go to space and actually do science.”

Ferl, a professor in UF’s Horticultural Sciences Department, Director of the Astraeus Space Institute, and Assistant Vice President of Research, became one of the first space biologists to fly alongside his own experiment — a moment that marked a new era in researcher-led missions. His suborbital journey provided a rare opportunity to study how terrestrial biology responds to the very first moments of spaceflight.

“For decades, space biology has relied on professional astronauts to carry out experiments designed by scientists on Earth,” Ferl explained. “But to truly understand how biology works in space, I believe you - as the scientist - have to be there. You have to feel the environment.”

This September, Ferl and longtime collaborator Anna-Lisa Paul, Ph.D., will be back at Blue Origin’s West Texas launch site, continuing their work with a new series of plant experiments. Ferl and Paul, who directs UF’s Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research and is a professor in Horticultural Sciences, are tracking fluorescently tagged genes in Arabidopsis plants to study how gene expression changes during the rapid shift from Earth’s gravity to the microgravity of spaceflight and back again. It’s a full-circle moment for Ferl, who remains deeply engaged in the same questions that sent him to space a year ago.

Unpacking the Transition from Earth to Space

Ferl’s experiment focused on the early metabolic responses of plants during the critical transition from Earth’s gravity to the weightlessness of space.

“The scientific community has accumulated plenty of data comparing biology in orbit with that on Earth,” he said. “But we’ve known almost nothing about what happens in those first few minutes as organisms enter space and are exposed to microgravity.”

Initial results from the flight reveal intense metabolic changes in the early moments of spaceflight. These changes are distinct from, but connected to, the long-term adaptations seen in orbit.

Early Findings, Future Impact

While the data from Ferl’s experiment are still on the way to being published, the findings are already shaping the direction of ongoing research. The work contributes to a growing understanding of how terrestrial life, from plants to humans, shares fundamental pathways in responding to the space environment.

“This has real implications for the future of space missions,” Ferl noted. “As we send more people and more biology into space in support of exploration, we need a comprehensive understanding of how living systems adapt — right from the start.”

Ferl and his team will return to Blue Origin’s launch site in Texas in September to continue their research, sending an uncrewed payload of plants into suborbital space. The flight carries no humans—but it does carry an automated experiment designed to advance their understanding of plant biology in space. It’s part of a broader effort to refine what Ferl calls “researcher-tended missions.”

-699x466.jpg)

A New Course for UF Space Science

The mission has not only shaped the trajectory of Ferl’s research, it has also energized Astraeus and the university’s space biology efforts.

“This is about building a new kind of science culture,” Ferl said. “One where the scientists are embedded in every part of the mission, from experiment design to the moment of launch.”

As the one-year anniversary of his flight approaches, Ferl remains focused on pushing the boundaries of what science in space can be. But he hasn’t forgotten the magnitude of the moment.

“Even a year later,” he said, “the most powerful thing I feel is just: thank you. Thank you for the chance to go, to see it for myself, and to bring that knowledge back to Earth.”