Violence alters human genomes for generations, researchers discover

In February of 1982, the Syrian government besieged the city of Hama, killing tens of thousands of its own citizens in sectarian violence. Four decades later, rebels used the memory of the massacre to help inspire the toppling of the Assad family that had overseen the operation.

But there is another lasting effect of the attack, hidden deep in the genes of Syrian families. The grandchildren of women who were pregnant during the siege — grandchildren who never experienced such violence themselves — nonetheless bear marks of it in their genomes. Passed down through their mothers, this genetic imprint offers the first human evidence of a phenomenon previously documented only in animal models. The genetic transmission of stress across multiple generations.

“The idea that trauma and violence can have repercussions into future generations should help people be more empathetic, help policymakers pay more attention to the problem of violence,” said Connie Mulligan, Ph.D., a professor of Anthropology and the Genetics Institute at the University of Florida and co-senior author of the new study. “It could even help explain some of the seemingly unbreakable intergenerational cycles of abuse and poverty and trauma that we see around the world, including in the U.S.”

While our genes are not changed by life experiences, they can be tuned through a system known as epigenetics. In response to stress or other events, our cells can add small chemical flags to genes that may quiet them down or alter their behavior. These changes may help us adapt to stressful environments, although the effects aren’t well understood.

It is these tell-tale chemical flags that Mulligan and her team were looking for in the genes of Syrian families. While lab experiments have shown that animals can pass along epigenetic signatures of stress to future generations, proving the same in people has been nearly impossible.

“Resilience and perseverance is quite possibly a uniquely human trait.” —Connie Mulligan

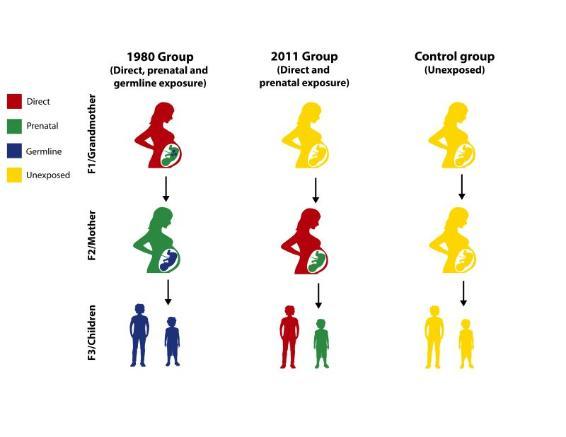

Mulligan worked with Rana Dajani, Ph.D., a molecular biologist at Hashemite University in Jordan and co-senior author, as well as anthropologist Catherine Panter-Brick, Ph.D., of Yale University, to conduct the unique study. Dajani envisioned the research project; because of her intimate knowledge of the Syrian population and its tragic history, she designed the study to cover three generations of Syrian refugees to Jordan. Some families had lived through the Hama attack before fleeing to Jordan. Other families avoided Hama, but lived through the recent civil war against the Assad regime.

The team collected samples from grandmothers and mothers who were pregnant during the two conflicts, as well as from their children. This study design meant there were grandmothers, mothers and children who had each experienced violence at different stages of development.

A third group of families had immigrated to Jordan before 1980, avoiding the decades of violence in Syria. These early immigrants served as a crucial control to compare to the families who had experienced the stress of civil war.

Study coauthor Dima Hamadmad, a Syrian researcher and the daughter of refugees, led the search for families that met the study criteria and collected cheek swabs from 138 people across 48 families. "The participants took part in the research out of love for their children and concern for future generations,” she said. “But more than that, they wanted their stories of trauma to be heard and acknowledged.”

Back in Florida, Mulligan’s lab scanned the DNA for epigenetic modifications and looked for any relationship with the families’ experience of violence.

In the grandchildren of Hama survivors, the researchers discovered 14 areas in the genome that had been modified in response to the violence their grandmothers experienced. These 14 modifications demonstrate that stress-induced epigenetic changes may indeed appear in future generations in humans, just as they can in animals.

The study also uncovered 21 epigenetic sites in the genomes of people who had directly experienced violence in Syria. In a third finding, the researchers reported that people exposed to violence while in their mothers’ wombs showed evidence of accelerated epigenetic aging, a type of biological aging that may be associated with susceptibility to age-related diseases.

Most of these epigenetic changes showed the same pattern after exposure to violence, suggesting a kind of common epigenetic response to stress – one that can not only affect people directly exposed to stress, but also future generations.

“We think our work is relevant to many forms of violence, not just refugees. Domestic violence, sexual violence, gun violence: all the different kinds of violence we have in the U.S,” said Mulligan. “We should study the effects of violence. We should take it more seriously.”

It’s not clear what, if any, effect these epigenetic changes have in the lives of people carrying them inside their genomes. But some studies have found a link between stress-induced epigenetic changes and diseases like diabetes. One famous study of Dutch survivors of famine during World War II suggested that their offspring carried epigenetic changes that increased their odds of being overweight later in life. While many of these modifications likely have no effect, It’s possible that some have functional effects that can affect our health, Mulligan said.

The researchers published their findings, which were supported by the National Science Foundation, Feb. 27 in the journal Scientific Reports.

While carefully searching for evidence of the lasting effects of war and trauma stamped into our genomes, Mulligan and her collaborators were also struck by the perseverance of the families they worked with. Their story was much bigger than merely surviving war, Mulligan said.

“In the midst of all this violence we can still celebrate their extraordinary resilience. They have persevered,” Mulligan said. “That resilience and perseverance is quite possibly a uniquely human trait.”