What is the history behind growing rice in the Everglades?

Rice was grown in the Everglades Agricultural Area for a brief period in the 1950s, but it was limited to about 2,000 acres (800 hectares).

Then came the discovery in Florida of a rice virus called hoja blanca, or white leaf, which stunts the plants or even kills them. This virus was first reported in the late 1950s in Colombia and Venezuela.

Rice made a comeback in Florida in 1977 after growers in the Everglades Agricultural Area demonstrated that it could be grown in sugarcane fields during the summer fallow period from May to August – when it is too hot and wet in South Florida to grow vegetables. By this point, the hoja blanca disease was under control, and new resistant varieties of rice had been developed.

During late spring and summer, more than 50,000 acres (20,000 hectares) of fallow sugarcane land in the Everglades Agricultural Area is available for rice production. In 2023, about half of these acres were planted with rice. The remaining land either remains fallow or is flooded but bears no rice – a practice commonly referred to as “fallow flooding.”

On average, each acre that is cultivated yields about 2 tons (1,800 kilograms) of rice.

What makes rice cultivation in this area different?

Rice cultivation in the Everglades Agricultural Area area does not require any starter nitrogen, phosphorus or potassium fertilization because the regional soils are highly organic and rich in nutrients.

The area is comprised of nearly 450,000 acres (180,000 hectares) of organic soils known as Histosols. These soils contain up to 80% organic matter, making them unique to the region and a vital resource to its vibrant agricultural economy. Histosols are also sometimes called bog or peat soil.

The Histosols of South Florida formed over a period of several thousand years when organic matter built up faster than it could decompose in the flooded sawgrass prairies that flourished in the area south of Lake Okeechobee.

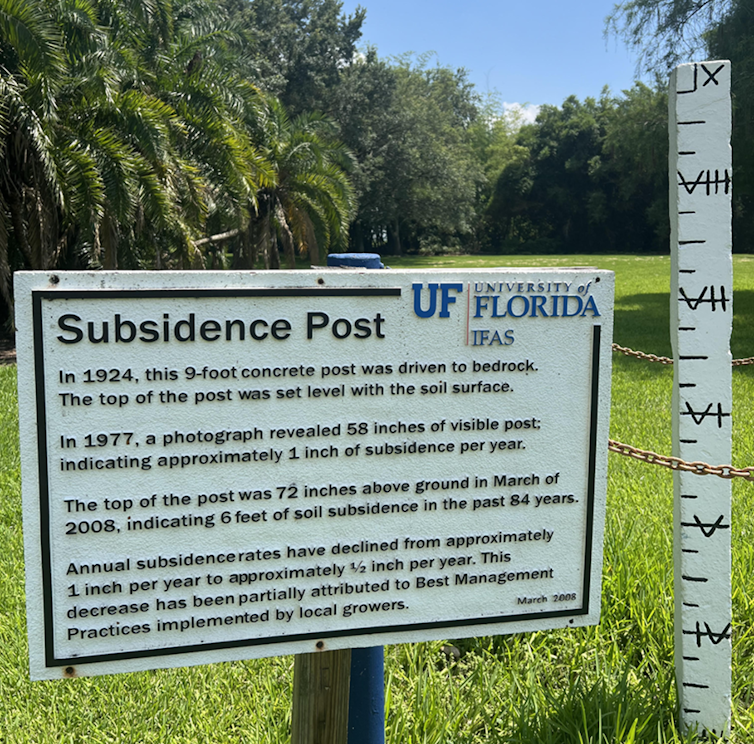

But since the land here was drained for crop production in the early 1900s, organic material has been decomposing faster than it is replaced. This is primarily due to microbially mediated oxidation. It happens when organic matter is slowly disintegrated and consumed by microbes. This results in the gradual loss of soil and lowering of the surface elevation.

The soil depth in this area varies between a few inches to up to 5 feet. Under the Histosols lies hard limestone bedrock that is not conducive to farming. In many places, the limestone bedrock gets exposed at the surface, or pieces of it get incorporated into the soil.

What does growing rice do for the soil health there?

By flooding these fields for prolonged periods, growers suppress both the microbial activity that causes oxidation and the hatching of pest insects. It also increases the water-holding capacity of the soil, which allows for more moisture retention during drier periods of the year.

The improved soil health benefits the sugarcane crop and maximizes the longevity of the soil.

Growing flooded rice has also proved to attract wading birds like great white heron, snowy egret and glossy ibis.

What work is your team doing now?

Over the past 15 years, more rice and more varieties of rice have been planted. While only two dominant varieties were planted in 2008 across about 12,000 acres (4,800 hectares), more than 10 varieties were planted across 23,000 acres (9,300 hectares) in 2023.

To provide a continual supply of new varieties, researchers and others at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, along with Florida Rice Growers Inc., conduct annual rice variety trials to rate new or existing varieties in South Florida. The trials aim to identify high-yielding, disease-resistant rice varieties that are compatible to the area’s subtropical climate and highly organic soils.

Every summer, the University of Florida IFAS Extension and research faculty conduct a rice field day dedicated to showcasing their current research.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.