UF polymers can be catalyst for new era in manufacturing

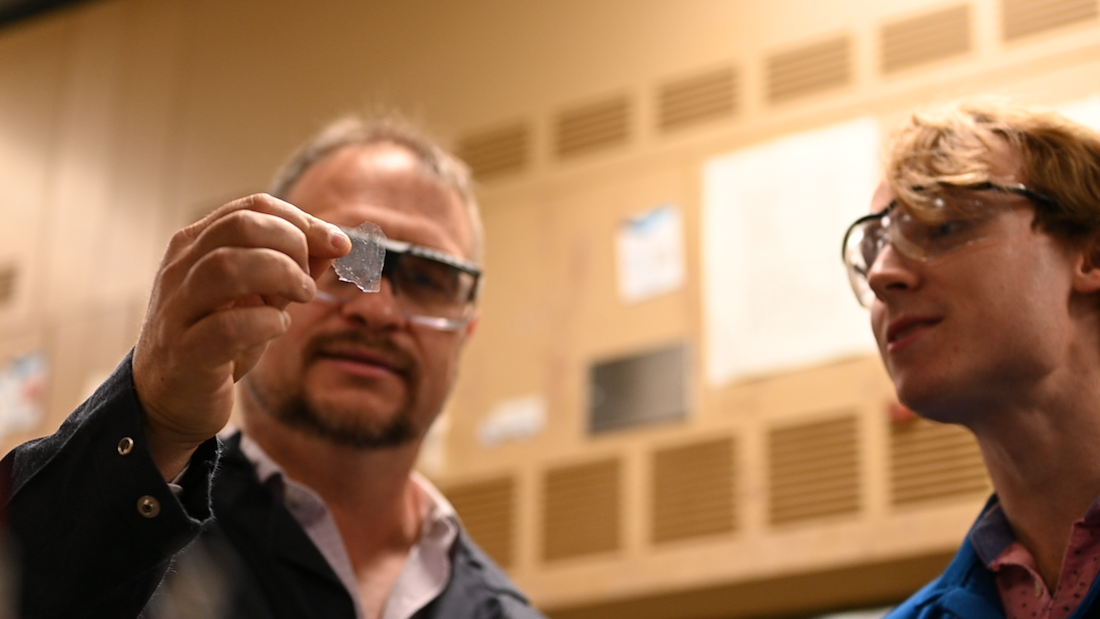

Adam Veige, Ph.D., professor inorganic chemistry

One company with origins tracing back to a University of Florida laboratory is working to create a future where drug therapies come with fewer side effects, water bottles don’t have toxic nanoplastics or additives and vehicles can be more energy efficient.

Oboro Labs, Inc., a new UF startup, is commercializing a patented catalyst enabling the mass production of cyclic polymers, discovered by The Veige Research Group in UF's department of chemistry led by Adam Veige, Ph.D. This revolutionary discovery could change the way global manufacturers produce and deliver some of the products used worldwide.

“Use cases could be low-friction coatings for saving fuel, money, and the environment,” said Oboro Labs CEO Gregory Kis, “or printable wire, which is lighter, cheaper, faster, easier to produce and would not require the mining of precious metals.”

Kis and Veige envision more targeted drug delivery, reducing side effects in patients. They see a way to eliminate the plastic nanoparticles present in disposable water bottles and other packaging. Their discovery could reduce friction on surfaces – and make lighter weight, more-efficient electronic materials possible.

“Cyclic polymers are better for consumers, businesses, and the environment. The examples go on and on,” Kis continued. “Virtually no industry would be untouched – infrastructure, medical devices, drug delivery, power supplies, health and beauty, etc. It’s nearly endless.”

Currently, these industries use linear polymers in their products, which at the molecular level have chain ends. These chain ends break down, which is why we hear about nanoparticles in our water bottles or why we need to change the oil in our cars. But cyclic polymers have no chain ends. They have lower friction when attached to surfaces, can be electrically conductive, and have higher operating temperatures and heat tolerances.

“We are at the forefront of a polymer evolution,” said Veige. “The first wave of polymers and plastics in the 1950s and ‘60s changed the quality of life on the planet forever.

“The next wave of materials will further improve that quality with an eye toward improved sustainability, energy efficiency, and performance,” he continued. “Cyclic polymers are poised to lead that new wave of advanced materials, and Oboro Labs in partnership with UF is able to make it happen.”

Oboro’s technology is protected by more than 20 patents filed by The University of Florida Research Foundation. Currently, Oboro is ready to sell the catalyst that makes the cyclic polymers on the open market and conduct collaborative research with its partners. With plans for expanded facilities, Oboro will be able to sell specific polymers in quantity shortly. For more information on Oboro Labs, Inc. please visit Oboro Labs or contact the company directly at info@oborolabs.com.