Decades ago, long before gene therapy was on the public's radar, University of Florida (UF) scientists were meticulously working toward a breakthrough.

Now technologies such as adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based gene therapy, which delivers new genetic material to human cells, have been transferred to all areas of the medical sphere-from pharmaceutical companies to healthcare facilities. Doctors are treating genetic diseases on an international scale and jobs are being created, all because of professors and students at a state university who have vision (and the resources to execute it). This is the power of tech transfer; it creates a life-changing ripple effect across the global landscape.

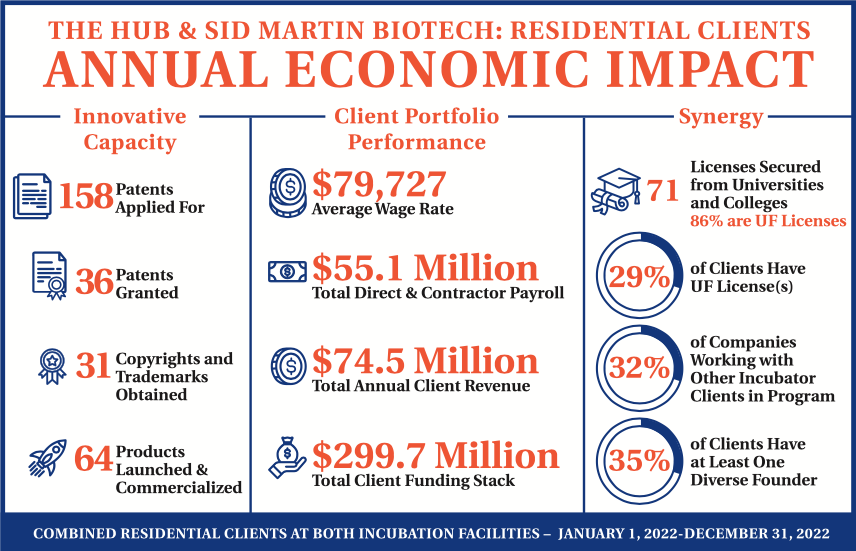

UF Innovate has served as a model for universities nationwide looking to further their tech transfer efforts. UF connects innovators with entrepreneurs, investors and industry experts, while its business incubators (The Hub and Sid Martin Biotech) take research discoveries from the laboratory to the market. Since its inception in 1995, UF Innovate has generated more than $10.4 billion in private investments, launched upwards of 300 startups via tech licensing, and created 7,900-plus startup jobs.

One prime example of this success can be found in Alachua, Florida, which is only a short drive from the UF campus in Gainesville. There, the power of tech transfer is in full force with an AAV-based gene therapy company called Lacerta Therapeutics, which is known for providing novel therapies to people with rare genetic disorders. Lacerta was born in UF's Sid Martin Biotech incubator six years ago, and its growth has resulted in about 1,000 Alachua-based jobs.

"Lacerta is an example of what happens when cool tech comes out of a university, we incubate and massage it a bit, and we offer guidance and industry knowledge that leads to business success," said Jim O'Connell, the assistant vice president for commercialization and the director of the office of technology licensing at UF. "Because of this, Alachua is becoming a center for biotech. We are showing what can be done in a given ecosystem and how we can build on the assets we have."

Backed by about $20 million in annual funds from Gatorade (which was also created in a UF lab in 1965), UF's tech transfer initiatives have more financial leverage than those at many other research universities. Judicious reinvestment of these funds helps create a platform for the future of tech transfer and economic development (see sidebar about how universities without this financial advantage can still support successful tech transfer programs).

"Patents, for example, are really expensive, and quite a few universities in the country don't even have a patent budget. So, when these universities come up with something patentable, they have to beg for funds from deans and central administration, whereas I have people on my team that directly make those decisions every day," O'Connell said. "If you have millions to reinvest, it certainly makes the job easier. But, for those universities that don't, the key is to reinvest wherever you can-into the whole system, even if that is just starting with hiring the best people you can."

The return on investment from channeling funds into university tech transfer programs throughout the nation is clear. Alachua-which is often described as a "sleepy" town of less than 11,000 people-is proof. The small Florida city is now drawing attention from massive Fortune 500 companies because of the booming presence of Lacerta and other up-and-coming startups based on UF technology.

Dr. Edgardo Rodriguez-Lebron, the CEO/ co-founder of Lacerta, holds multiple patents in AAV technology and a Ph.D. in neuroscience from UF. He has transitioned from the UF student labs to professorship to running his own company.

Rodriguez-Lebron has conducted cutting-edge research on Huntington's disease, spinocerebellar ataxias and other neurodegenerative diseases. He has also secured tens of millions of dollars to fuel Lacerta's commitment to finding a cure for rare central nervous system diseases. Rodriguez-Lebron first decided to pursue his graduate studies at UF after learning about the groundbreaking work the faculty had been conducting on genetic technology.

"This was back in 1997, when we were just finishing sequencing the human genome and nobody knew what AAV therapy was. I realized this was the future of genetic medicine and I became obsessed, so I applied to UF to come work on the technology," Rodriguez-Lebron said. "UF has really played a pivotal role in propelling this technology that I bet my life and career on. Now it's my responsibility to realize the potential of these technologies, and to use them to impact and change people's lives."

The career path Rodriguez-Lebron took is one now being followed by current generations of UF researchers. For example, Rodriguez-Lebron recently brought three UF neuroscience students (who had researched AAV therapies for Friedreich's Ataxia) to Lacerta to work on developing a new medicine for this degenerative nervous system disease.

"These students beat out a bunch of big companies like Pfizer with their research, and now we are the leading developer for this product," Rodriguez-Lebron said, adding that the drug should be in clinic by May 2024. "This is really quite the story in terms of how Lacerta's geographical location (and the proximity to UF) allowed us to be extremely competitive with big drug companies. This will be the first product that Lacerta is bringing to the clinic that was fully conceived here."

This further demonstrates that the impact of tech transfer on individual lives is being widely felt-from the student and faculty researchers who develop treatments at UF, to the patients and healthcare professionals who benefit from these technologies, to the cities that grow because of the economic boon, to the employees of the companies that produce these products.

"We've been able to infuse this brand new energy of youth and high-paying jobs into Alachua because of our partnership with UF, which incentivizes this city and promotes the state economy," Rodriguez-Lebron said. "I think universities are starting to realize the potential they have when it comes to these tech transfer initiatives, and the broader impact they can have on the national landscape."

MAKE CONNECTIONS.

A university's alumni and donor connections in the tech industry are often under-leveraged. Reaching out to individuals in the venture capital or pharmaceutical fields can come with free advice and potential donations.

BUILD A MENTORING NETWORK.

Tech entrepreneurs and mentors-inresidence can provide critical guidance to a university. "These individuals can help screen technologies, and even create business models to wrap around these technologies, sometimes for free," O'Connell said.

CREATE THE CULTURE.

Culture starts at the top, with upper administration being supportive of tech transfer initiatives. "That support trickles down into everything, and there needs to be an understanding that there's value in the long-term results of these programs," he said.

REINVEST FUNDS.

Even universities with smaller tech transfer budgets can efficiently reinvest funds. The first step is to make sure the royalty distribution policy is structured so that a fair portion of that money goes back to the tech transfer office. "If you can't pay for patents and don't have quality people, you're never going to get the best deals," he said.

FOCUS ON THE BIGGER ECONOMIC PICTURE.

Universities are absolutely essential to growing new parts of an economy. "Every single geographic center of innovation starts with universities," he said.