There was a time when new students at the University of Florida received a punch card containing all of their class information. The punch card allocated only a limited number of letters for their first and last name.

In 1962, a newly admitted student received one of those cards.

“John Williams,” it stated. The card listed the student’s classes and housing: a boys’ physical education class and a room in a boys’ residence hall.

Except, that “John Williams” did not exist. Johncyna Williams was her name. And she, along with her would-be roommate, was about to make history.

It had been several years since the Florida Supreme Court ordered UF to desegregate its graduate and professional schools. But UF would not integrate its undergraduate student body until 1962 — the same year Johncyna and six others began their studies at UF.

“I had no clue at 17 – 18 years old,” Johncyna said. “It’s a college. I didn’t know there weren’t other African American students at the time.”

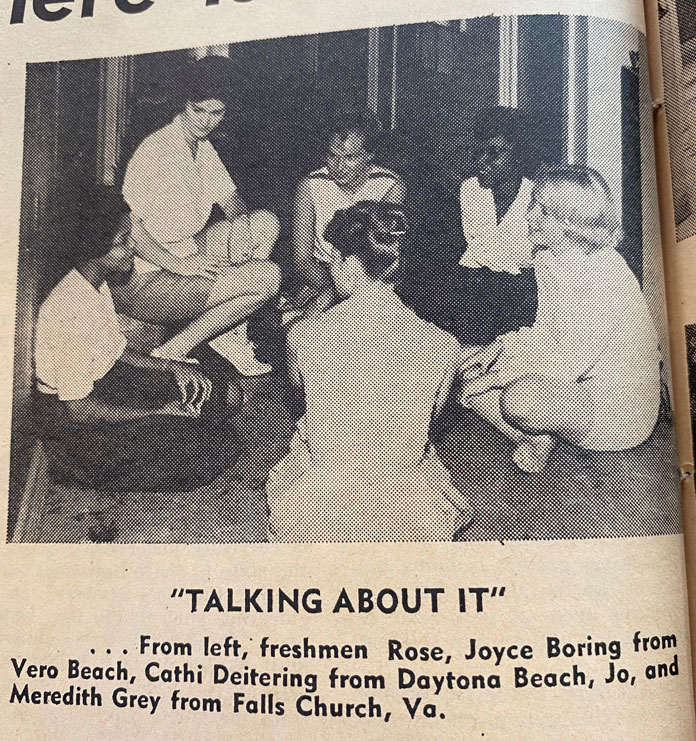

With help from the “dorm mother” for Mallory Hall, Johncyna’s punch card information and housing were corrected. When she met her roommate, Rose Green, the two girls realized they were among the first Black undergraduate students at UF.

Thirteen years prior, six African Americans were denied admission to UF. This resulted in a lawsuit against the university, and in the following years, the movement to desegregate Florida’s universities reached the Supreme Court of the United States.

In 1956, the Supreme Court ruled that Virgil Hawkins, the only remaining petitioner of the lawsuit, was entitled to prompt admission to UF. In 1958, Hawkins withdrew his application to the College of Law in exchange for UF’s desegregation.

W. George Allen became the first African American to graduate with a law degree from UF in 1962.

Allen had come to Johncyna’s still-segregated high school encouraging students to apply to UF. He told them other applications from Black students had been “lost” and taught them how to send them by certified mail.

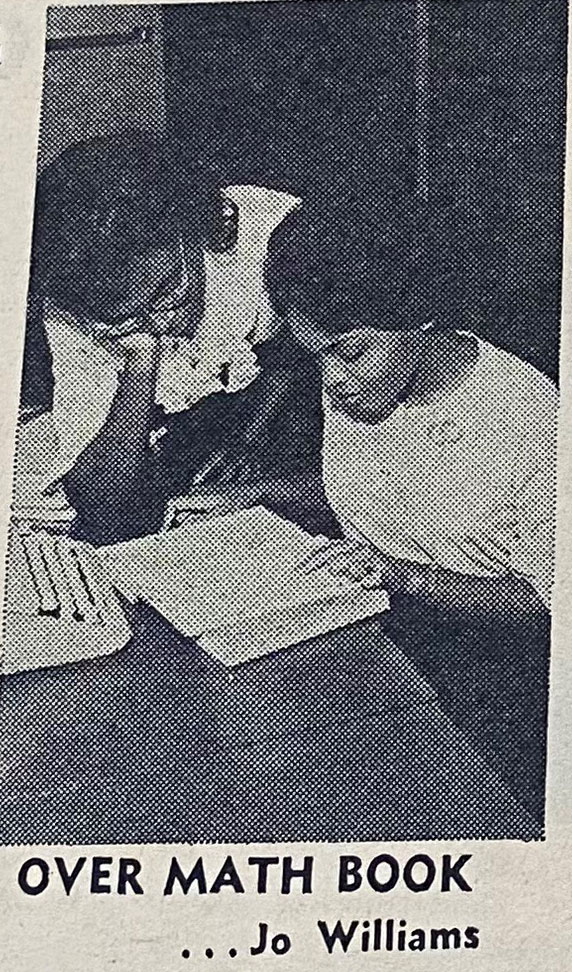

A newspaper clipping from The Alligator October 7, 1962.

“Several of my classmates were accepted, but a few of them wanted to do a home economics degree,” she said. “Florida didn’t have that at the time. I was as excited as anyone else that I was accepted. The school counselor told me to do it.”

She and one other girl from Lincoln Memorial High school in Palmetto, Florida, came to UF that fall as freshmen.

Johncyna adjusted to student life at UF. She lived in Mallory Hall all four years while getting a degree in education. She and her roommate, Rose, also went to some football games.

“Only a couple because I am not too into sports,” she recalled. “One was an Alabama game. They’re Roll Tide? They kept chanting that and had the Confederate flag waving. Rose and I said, ‘So much for football.’”

Living under the same roof allowed for Johncyna’s white peers to become comfortable in asking what she referred to as “curious questions.” One asked her if the NAACP was paying for them to attend UF. To which Johncyna replied, “I wish they were!” Another told her she previously had never spoken to a Black person.

Johncyna attended her first Broadway show on the UF campus. She and her floormates went to see a traveling group perform “The Sound of Music.” She still exchanges Christmas cards with the girl who was two doors down. She now lives in Massachusetts.

As the years went by, more African American students enrolled. Johncyna became friends with Geraldine Williams, the first Black graduate of the College of Journalism and Communications. They hung out together and attended local high school football games.

A newspaper clipping from The Alligator October 7, 1962.

Throughout her time at UF, Johncyna kept her sights on her dream of becoming a teacher. She came from a long line of teachers in Manatee County, Florida. Her mother taught for more than 40 years in Bradenton and played an active role in their church and community. Her uncle was the superintendent of Black secondary education in Florida.

Through her education studies, Johncyna interned at P.K. Yonge Developmental Research School.

“I learned a lot,” she said. “It was a really good experience.”

In 1966, Johncyna graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Education. Out of the original seven who integrated the campus, Stephan Mickle finished first in 1965, having done a year at a previous school. Johncyna is unsure if any of the others finished. Her roommate, Rose, transferred to a different school, seeking a more traditional historically Black college or university experience.

Not obtaining a degree from UF wasn’t an option for Johncyna, however.

“My parents were paying for this,” she said. “I knew I had to get my degree and get a job. Whatever came up (at UF), I had to deal with it.”

Ultimately, Johncyna worked as a teacher in Manatee County for five years before getting married to Hal McRae, a professional baseball player. Hal’s career totaled 42 years in the MLB with 19 of them as a player and the others as a coach and then a manager. They are now both retired and living in Bradenton.

“All in all, it wasn’t a bad experience. It helped to be young and naive,” Johncyna said. “Looking back, I got the education my parents wanted me to get.”