Why we love Wordle, according to science

Why we love Wordle

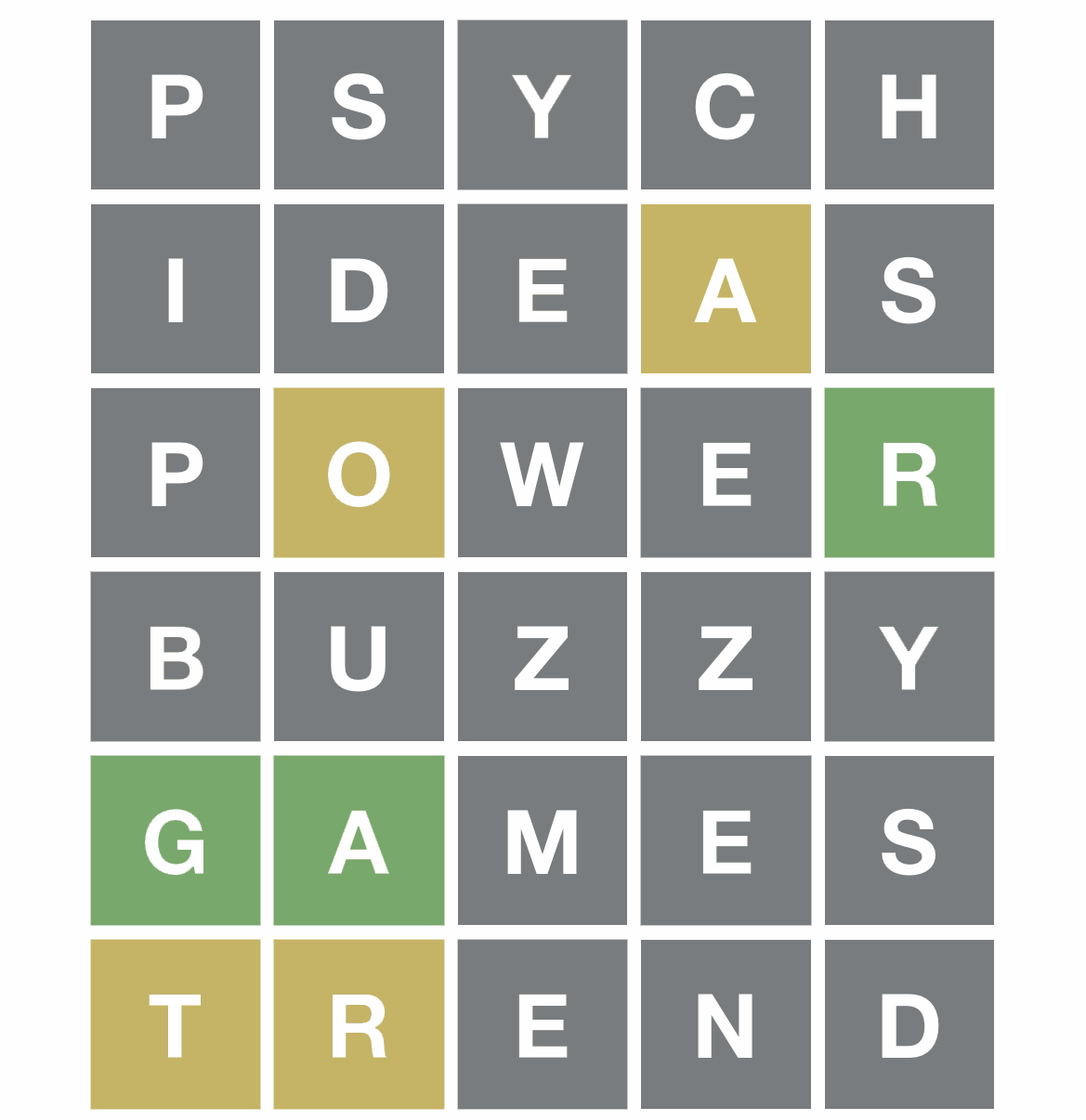

Social psychologist Matt Baldwin wakes up thinking about the yellow and green boxes of Wordle, the free, once-a-day word game that has gained millions of fans since its public launch in October. Unlike most players, though, he understands why our brains crave it.

Baldwin, a University of Florida professor, points to several psychological concepts that may explain our infatuation with the simple but sharable game.

It delivers an ‘aha’ moment (even if you lose)

The moment at the end of the puzzle when the answer is revealed delivers what psychologists call a sudden influx of fluency — something we’re hard-wired to pursue, Baldwin explains.

“Even when you don't get it, and the answer is revealed, finding that solution feels good," he said. "That feeling of fluency is something that we seek out not only in games, but also when we're trying to solve a problem in our work or in our relationships.”

It suits our pandemic-addled minds

Entering year three of the pandemic, “we're overwhelmed. Things can't hold our attention because we're so bombarded with COVID stuff,” Baldwin said.

Wordle can be an ideal way to create flow, the pleasurable immersion we feel when tackling an activity with the right combination of meaning and challenge.

“It’s not too easy or too hard, and it doesn’t demand too much attention. It’s also sort of purposeful: It feels like you’re training your brain, not just stacking blocks or launching a bird,” he said. “It captures meaning and attention at that optimal level. I think that's what makes it really special.”

It’s shared

Ever like a band that no one seems to know about, then get excited when you meet someone who loves them too? That’s the essence of shared reality theory — our subjective preferences feel validated when someone else shares them. With its built-in sharing function, Wordle provides just such an experience, Baldwin said.

“We like to tune our internal states to the internal states of others. I may think Wordle is fun, but when I see that everyone else on Twitter thinks it's fun, then it’s like it becomes an objective fact,” he said.

It’s bingeproof

Because Wordle is only offered once a day, “it’s possible that it keeps the feeling from becoming too basic or too familiar,” Baldwin said. “The scarcity of this insightful moment may be something that keeps it interesting.”

It satisfies our urge to fit in with peers

If your Twitter network is into Wordle, you’ve likely seen someone tweet that they’ve “given in” and started playing. That’s peer pressure, but peer pressure isn’t inherently bad, Baldwin said. The concept of in-group identity can help us bond with others.

“Norms give us the ability to tune our attitudes, beliefs and identities to that of other people in our group. It gives us something to coalesce around and helps form a collective identity,” he said.

For Baldwin, that’s a distributed community of scholars who happen to be very into Wordle right now. If you opt out, you feel less connected to the group.

“If I don't play Wordle at this point, what kind of academic am I?” he joked. “Sharing it on Twitter is a way of saying like, ‘look at me, I'm also doing Wordle just like everyone else.’ That makes me a good group member.”

It shows how we stack up

Sharing your daily Wordle score doesn’t just signify you’re part of the group, it shows how you performed, which offers an opportunity for social comparison. For better or worse, Baldwin said, we love social comparison.

“Comparison can be detrimental to self-esteem if you're always comparing upward to people who are unattainable. But I can learn something about myself by the way I stack up against others, and it doesn't always have to be a negative feeling. Maybe people just like the information they get from looking at what other people are doing and getting a sense of where they stand.”

Stack these concepts on top of each other, and Wordle’s exponential growth begins to make sense. It’s about more than guessing a five-letter word.

“Shared experiences give a lot of meaning to life,” Baldwin said. “They help us orient toward what's good, what's meaningful and what's worthwhile.”