Untangling the knots in the supply chain

Disruptions to the nations supply chain continue to affect consumers as the holidays approach.

Welcome to From Florida, a podcast where you’ll learn how minds are connecting, great ideas are colliding and groundbreaking innovations become a reality because of the University of Florida.

Disruptions in the supply chain have impacted consumers’ ability to get a wide range of products, from couches to milk. Asoo Vakharia, the McClatchy professor and director of the Supply Chain Management Center in UF’s Warrington College of Business, explains what’s happening, what consumers can do and what companies should do in this episode of From Florida.

Nicci Brown: Welcome to From Florida where you'll learn how minds are connecting, great ideas are colliding and groundbreaking innovation is becoming a reality because of the University of Florida. I'm your host, Nicci Brown.

Today, we are going to talk about something that is affecting so many of us in ways we never even considered: the disruption of the supply chain, both globally and nationally. We're joined by Professor Asoo Vakharia, the McClatchy Professor and Director of the Supply Chain Center in UF's Warrington College of Business. Asoo also is a fellow of the Decision Sciences Institute and the Production and Operations Management Society. Asoo, thank you for joining us.

Asoo Vakharia: You're welcome, Nicci. Thank you for inviting me.

Asoo Vakharia, the McClatchy professor and director of the Supply Chain Management Center in UF’s Warrington College of Business

Nicci Brown: I think it's fair to say that many of us never gave the supply chain a second thought, that is until the past year when long waits developed for major products, such as refrigerators and couches and even simple things like grocery items became harder to get. So, let's start with the basics. What is the supply chain?

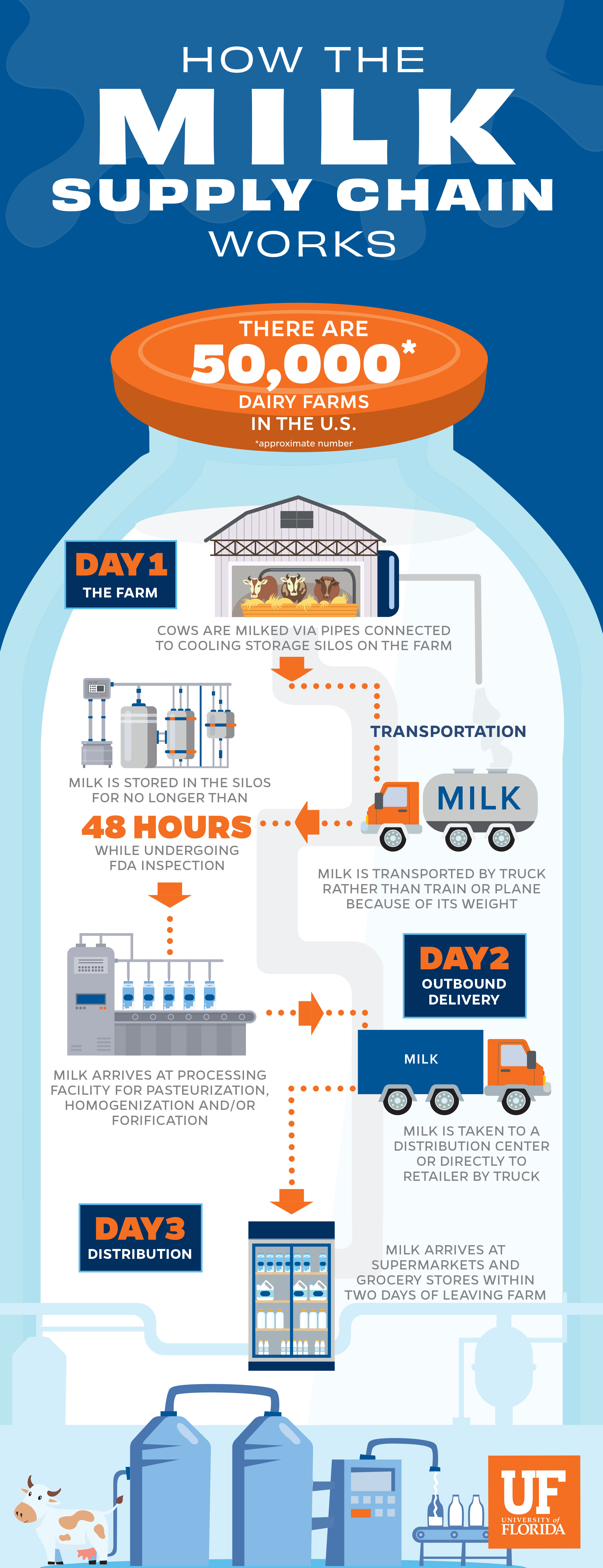

Asoo Vakharia: To understand it, perhaps taking the example of a product, milk, we all use on a regular basis might be helpful. So, I tend to think of a supply chain as three different positions that are occupied before we get the product. The first position is who produces it. And in this case, it's farms, and there are about 50,000 farms in the United States producing milk. All right. These farms store the milk for at most 48 hours. And then it's put on trucks to be sent to, I guess, processing centers. That's where the homogenization as well as pasteurization takes place.

And then once that's complete, then it's sent again on trucks to, maybe, a distribution center, or a Publix distribution center in Jacksonville or maybe directly to Publix's retail outlet. All of this actually is really interesting to observe because it's supposed to happen in about two and a half days after the milk is produced. So that, in a nutshell, is the supply chain. We've got the source, the farms, we've the processing stage where we homogenize milk and pasteurize it, and then we got the retail outlet, which is the place where we go ahead and buy it.

Milk goes through a series of steps before consumers get the product.

Nicci Brown: Is it accurate to say the pandemic set off supply chain disruptions or was this a problem simmering out there before March 2020?

Asoo Vakharia: This is a really interesting question because when you say the pandemic set off disruptions. Yes, it did. That's a short answer, but anything can set off a disruption. And disruptions are a way of life. If I'm a supply chain manager, I'm a supply chain operator, whatever pain point I'm at, even a consumer, disruptions are faced by us all the time. I mean, we saw this with the great toilet paper shortage maybe around March of last year or April of last year. So, I think this is happening all the time. What's unusual about the pandemic is three or four things. One is it was the scale effect was significantly higher. So, what happened was demand dropped so quickly and at such a high volume that it created a problem for us. The second thing was that over and above the demand stage, everybody sort of shut down.

So, we had what's going to be known today to us as The Great Resignation, which is actually a great reduction in employment. The second part is most of this got impacted on an international scale. So, it wasn't limited to a region of the world where we could deal with it in that region. It happened everywhere. The third thing is we don't know when it's going to end, okay, because I think there's this recurrence that's taking place in terms of the Delta and the Omicron [variants]. So, I don't know that the pandemic is over. And finally, is it going to reoccur frequently because if it is, then we have this issue about dealing with problems of this type over and over again. So again, the short answer, yes, the pandemic caused a disruption, but it's part of a supply chain is encountering disruption. The scale here was significantly bigger.

Nicci Brown: And I'm guessing that the shortages of workers and materials is a bigger factor in the disruption of the national supply chain, especially food items and household goods.

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, I would tend to agree with that to some extent because there is the sort of notion that everything within the country shut down. But if you actually take the global footprint of a supply chain, this was something that everybody also shut down. It wasn't only us. So, when we say shortage of material, shortage of this, that. Yes, but it's part of this entire supply chain which we expanded on a global basis. And so that's why this whole thing is being felt by us and every part of the world. It's not only the United States. It's just that we are paying a lot more attention to it.

Nicci Brown: Is it accurate to say the pandemic set off supply chain disruptions or was this a problem simmering out there before March 2020?

Asoo Vakharia: This is a really interesting question because when you say the pandemic set off disruptions. Yes, it did. That's a short answer, but anything can set off a disruption. And disruptions are a way of life. If I'm a supply chain manager, I'm a supply chain operator, whatever pain point I'm at, even a consumer, disruptions are faced by us all the time. I mean, we saw this with the great toilet paper shortage maybe around March of last year or April of last year. So, I think this is happening all the time. What's unusual about the pandemic is three or four things. One is it was the scale effect was significantly higher. So, what happened was demand dropped so quickly and at such a high volume that it created a problem for us. The second thing was that over and above the demand stage, everybody sort of shut down.

So, we had what's going to be known today to us as The Great Resignation, which is actually a great reduction in employment. The second part is most of this got impacted on an international scale. So, it wasn't limited to a region of the world where we could deal with it in that region. It happened everywhere. The third thing is we don't know when it's going to end, okay, because I think there's this recurrence that's taking place in terms of the Delta and the Omicron [variants]. So, I don't know that the pandemic is over. And finally, is it going to reoccur frequently because if it is, then we have this issue about dealing with problems of this type over and over again. So again, the short answer, yes, the pandemic caused a disruption, but it's part of a supply chain is encountering disruption. The scale here was significantly bigger.

Nicci Brown: And I'm guessing that the shortages of workers and materials is a bigger factor in the disruption of the national supply chain, especially food items and household goods.

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, I would tend to agree with that to some extent because there is the sort of notion that everything within the country shut down. But if you actually take the global footprint of a supply chain, this was something that everybody also shut down. It wasn't only us. So, when we say shortage of material, shortage of this, that. Yes, but it's part of this entire supply chain which we expanded on a global basis. And so that's why this whole thing is being felt by us and every part of the world. It's not only the United States. It's just that we are paying a lot more attention to it.

Nicci Brown: So, let's focus on the global picture. Would you give us an overview of the major ports in the United States and where they are and who runs them?

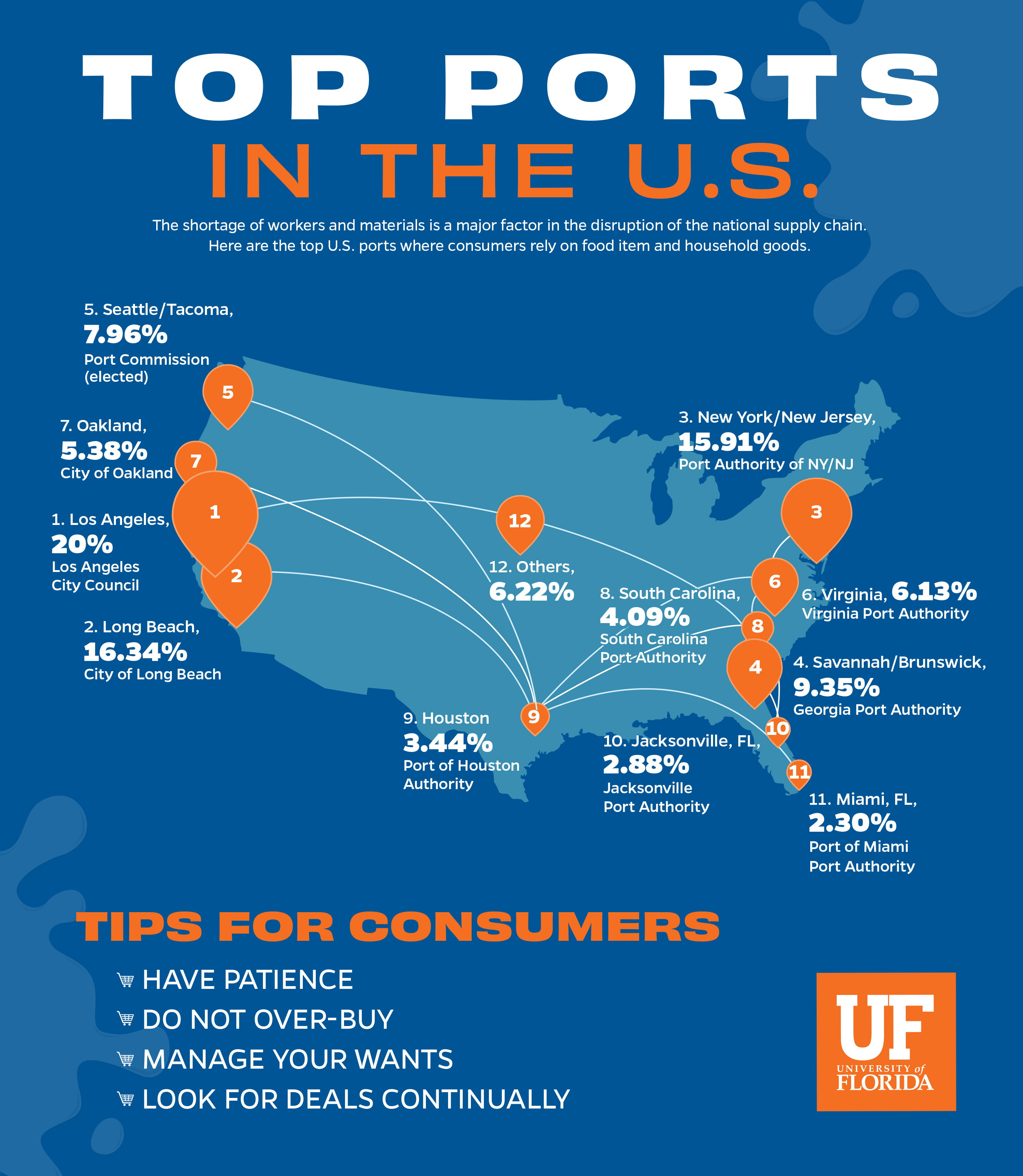

Here are the top U.S. ports where consumers rely on food item and household goods.

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, I think the very simple way of looking at that is just do a very quick scan of all the imports that come into the United States. And you'll see that approximately 20% are coming in from Asia and they are downloaded at LA. So that's the big port, right, in terms of scale. I think 20% of the entire volume in the U.S. is LA. The second big one is Long Beach, again, because the shipment is from Asia. It's about 13% of the total volume in the country. Both of these ports are run by the local city councils or the municipalities that are involved. So, there is very localized control here.

Now, if you go down the list, there are lots of smaller ports that emerge, okay. For example, New York/New Jersey is one, Houston is another, there is even Brunswick and Savannah, which are ports, but the scale effects compared to the imports coming in on the California side, which is LA and Long Beach, is significantly smaller, okay. Across the nation, it appears that there is local control or, for example, state control. So, for example, the Port Authority of New York, there's the Port Authority of Georgia and things like that. So those are the ones that control the ports. It's not federal control at all.

Nicci Brown: Is there anything the federal government can do to have a significant impact?

Asoo Vakharia: I think actually they've done what they can, but here is a problem that you encounter in most of these situations. You have a federal government which is probably trying to look at the collective good. Municipalities, ports, everything when it's run at the local and state level, there is an essential conundrum that emerges, which is that the collective wisdom of the federal government, which is looking at the collective country as a whole, is not sort of manifested at the local level. So, there is always going to be this tug of war. And yeah, sure. I mean, we did start to enforce a mandate that they should be open 24/7. But coupled with that, there were some other effects that happened. So, it's not exactly the federal government not doing things but there is a difference in terms of how whatever they do will be received by the local authorities.

Nicci Brown: And what were those other effects? Why didn't the 24/7 work the way that it was supposed to?

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, I think if you look at it from another perspective, it's the following. I try to think about this whole thing, and I talk about this in all my discussions with the execs and as well as my classes, think about a kitchen sink, okay. You have the inflows of the tap and you have the outflows of the drain, right. By doing the 24/7, all we did was we took that drain, which was maybe 18 or 12, made it 24/7, so it'd make it larger. So, the water that came into the sink from the tap is being processed faster, right.

Now, we didn't think about two things when we did that. One was, is there any change in terms of this magnitude of stuff coming in, that means the tap. How much have you opened it? And we kept opening it more and more and more. So, the water level actually didn't drop when you opened the drain. The second part is when you open the drain, at the bottom, there is a pipe. Now if that pipe is not expanded, right, simultaneously, the effects are going to be felt at the pipe now.

So essentially, we call it shifting bottlenecks. We have the drain at the bottleneck. We expanded the size and what happened was the pipe at the bottom, got to be the bottleneck. So, it's not that it didn't work. Of course, it worked. But now we've got containers on shore, which are lying to be picked up and all the ports are leaving these huge charges if people don't pick up the containers.

Nicci Brown: So, let's talk about Florida. How do Florida's ports fit into the nation’s supply chain infrastructure?

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, I think this is a really interesting question and I'm glad that we are talking about it a little bit because there's two things here that we should keep in mind. One is that when we discuss issues about Florida ports, first of all, from U.S. level, we're apart 5% of the total volume currently. So obviously we can always make the case saying, "Oh, we can have more capacity these ports." Now, what does more capacity mean? We need to have longshore people loading and unloading all the stuff that comes in.

We need to have an infrastructure which is a rail or trucks, which are going to visit these ports and take the goods of away from them because otherwise we're going to do the same thing we did in Long Beach, which is boats are going to be out there, we want to unload them, we do and then we have this huge set of warehouses where all the containers lie.

So, I think when you think about these types of issues, it's a little bit more complicated than it really appears to be — "Oh, we have capacity. Let's use it” — right, which is really the rationale that's being put forward. The other two parts here is that people might not be familiar with this, but most of the shipments are coming on what we call Ultra Large Vessels. These Ultra Large Vessels are about 14,501 TEUs (twenty foot equivalent unit) and above. Some of the ports on the Florida's side might not be able to handle those vessels. The second thing is to get them to Florida, you got to go through the Panama Canal. The Panama Canal does not handle Ultra Large Vessels. They handle Neopanamax and lower.

So, the idea is that you have to have smaller vessels coming in. If you have smaller vessels coming in the cost is higher. The third thing is if you don't have the infrastructure, how do we actually manage those ports? So, I think it's a very deep issue that you need to think about and try to entertain all the solutions to it before you suggest it as, I guess, a policy.

Nicci Brown: So, it sounds like it's not anything that could happen overnight, per se, but what about looking further into the future?

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, I think further into the future, actually, there's a unique solution that I don't know if, you know, it's just come out in the last five or six days or has been publicized in the last five or six days. The unique solution of the following. Amazon is a case in point. What they did is they actually went out and bought a lot of small vessels. They're shipping their whole products to over 42 centers in the U.S., not the two ports only. The second thing is because they have their own vessels and they're smaller, they can navigate the canal, they can get other places. And the idea is, costs are higher but at this point, the idea is to get the product to the people who want it. So, people seem to be willing to bear the costs, right? So, if you do this far-reaching analysis or thoughtful analysis at a more strategic level where you think about things in advance, they've done that in advance.

So now they're not facing the short. For example, they say that their shortage percentage jumped 15%, but the shortage originally were only about 1.5%. So, when you say 15% increase is not a significant percentage of that total volume. So, companies need to motivate this effort. We can have a simple solution. I mean, Walmart and Costco actually have jumped into the same process. So, we have examples of companies that are trying to do this and use the smaller ports as service points.

Nicci Brown: Do you think in a way, that's why we ended up, I mean, we had the perfect storm of the pandemic. But it seems that we had really gotten to the point where we had gotten so close to the bone in terms of not being able to stretch anything any further. So we were primed to be in this position and so now if we can avoid it in the future, it might mean having a little more padding in that supply chain.

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, absolutely. We call it building flexibility in the supply chain, making it more agile to respond to stuff. Technical terminology or whatever supply chain terminology. But the idea is that building in flexibility and building in additional slack or capacity indirectly is obviously warranted. But think about the shortage we have, for example, in trucking today. We don't have enough drivers. The containers that are offloaded and they're empty, they don't know where to put them.

So, the whole point is that, we are going to have these disruptions occur. The amount of padding that we build in will just drive our costs up, right, because, eventually somebody has to bear the cost. And the idea is that usually it's the consumer that everything is passed down to — not always the right thing to do, but that's what happens, right? So, if we do that, absolutely. But on the other hand, we got so used to certain products costing so little that now all of a sudden if you have to pay more, I wonder what our reactions are going to be.

So, unless there's a change in consumption patterns, I don't see this building capacity or flexibility as a solution.

Nicci Brown: What does the picture look like then in the months and even years ahead, based on your experience?

Asoo Vakharia: Yeah, I think that we can do several things and I think some of the stuff that we do is actually very much reasonable. I think the managers, if you look at most of the people, the executives that are running most of the companies, you'll see a marked shift over the last 10 years. About 30, 35% of them said disruption is the major issue. Today, it's almost 75 to 80% say "That's my major, major issue." Right? So, there's a mindset change. Other changes mindset changes in terms of technology. So, bringing technology to bear in some of these methods and implementation the supply chains, I think will probably have the positive impact for us going forward.

Like I keep saying, I don't want to go on to Amazon and so on, but even Walmart today recognized the shift in online buying that took place because of the pandemic. And they've seen that the shift is not going back. So, it's not like we are going to start going more to the store. It's just that we go to the store, maybe, but we will still continue buying online. So, trends like that are hard to, in some sense, go against the grain. I think the pandemic has changed a life set, and it's going to be a little time before we all can adapt to the new way to doing things and how best to serve a customer.

Nicci Brown: Well, speaking of time, when do you anticipate, or when can consumers anticipate an end to the supply chain issues that we're experiencing right now?

Asoo Vakharia: You’re going to put me out of a job if I have to respond to that question! I told you supply chain disruption is a way of life. So, I don't think we can have an end. We can have definitely an end to this current disruption that's happening and that's simply by recognizing that just because we handled one bottleneck, like the ports, operating them, there's going to be another one that comes up. So, we have this phenomenon of what we call shifting bottlenecks and that's going to keep happening. So, until everything stabilizes to the new surge in demand that's taking place, this is not going to be resolved.

And if you say timeline, it depends on the goods and the products. But I think that for certain product categories, for example, electronics, the ones that use the chips especially, is going to take a little bit longer because we are trying to build up the infrastructure locally to make those things. In fact, the federal government is making investments in that sector so that we have local capacity. Well, that's going to take a little while to pay off. So, it might even be the middle of next year. I think the most immediate stuff, we talk about toys all the time, we talk about stuff in the grocery stores, I don't see that as a major thing extending beyond February of next year simply because the demand will go down after the Christmas season. And so everything will get to a stable level. And then people will start planning ahead from February to the next year's December. And that lead time is enough for the supply chain to react and stabilize. So, I think that's the way I'm thinking about it.

Nicci Brown: And it sounds like even though there might be a little more diversification in terms of where we get things from, you don't see a huge shift in terms of us no longer bringing things in from global suppliers.

Asoo Vakharia: I think if it's left up to the people who manage the corporations, the companies and so on, there are very good reasons why we've gone international. It's not that in some sense it was a half-baked decision that, "Oh, we wanted to minimize, we already get something for 10 cents versus 15 cents." I think it was a very measured response. And I think it happened over time. So, I don't think you can correct for that immediately.

There is the idea of what we call insourcing now versus outsourcing, so basically getting stuff from closer. So, what we might do is the buffers or flexibility that you talked about building in earlier, we might build that in some location, which is much closer to where the customer is, right? But that's the real change that I see in the longer run. I don't see these supply chains disintegrating or new ones emerging. Of course, there are certain regions of the world that are so badly affected that they might suffer for a longer period of time than we have or we will.

Nicci Brown: And your advice to consumers, anything that you would share with us?

Asoo Vakharia: So, this is always hard to say. And I think that I don't know how to best put it, but I'll give you a couple of things. We've done this before, we are in this together. Let's not get on this bandwagon of, "I want this, I want that." Let's moderate our wants a little bit. Let's think logically. Let's realize that we can't solve the problem by ourselves. And please, please, please, don't go and do this toilet paper shortage for us again. I mean, just curtail your impulses and be a little bit thoughtful.

The second thing is yes, you will pay higher prices. But the part about high prices is I just read today, in fact, that a lot of corporations in 2022 are going to pay us higher wages. So, I know people say inflation, but wait a minute. If people are going to be back to the status quo in terms of the net effect, it's not too bad. Our incomes have gone up and costs have gone up, so, okay, we'll manage that.

And the third thing for consumers is look for deals continuously. There is lots of opportunity out there. People are offering stuff at good prices and maybe you won't get the brand you want, but you'll get a good brand. So, in terms of moderating what we do.

I wanted to end a little bit not with the consumer so much, but with the companies. If you think about what should we expect and what should people do. I think companies need to be a little bit careful here because the idea of a container from China to a port in the U.S. being $1,200 at one time and now costing $20,000. The idea that Maersk, which is the biggest shipping line in the world, is making exorbitant profits just on that big margin jump, is a little disappointing to see, to be totally honest.

To me, it looks like when we have a shortage of gas, the gas stations raise the prices to gouge us. So, I just would like the corporations to be a little hesitant. I think the best examples are, actually, if you look at pricing schemes and stuff, Walmart's gone up about 22%, Amazon about 25%. I think those are maybe some things that consumers can bear. But anything like what we've seen in the shipping lines is enormous. That level of profit — be a little bit thoughtful.

The second thing is, remember consumers have long memories and they will reward people who have a little bit recognition of our conditions, too. And finally, don’t do things short term. This financial return, I have to get a better return for my shareholders and stuff. Just be a little bit longer term and I think you'll come out ahead overall.

Nicci Brown: Great advice. Asoo, thank you so much for being our guest today.

Asoo Vakharia: You're welcome and thank you for inviting me.

Nicci Brown: Listeners, thank you for joining us for an episode of From Florida. I'm your host, Nicci Brown, and I hope you'll return for our next story of Innovation from Florida.