This microbe-crocheting engineer makes the invisible adorable

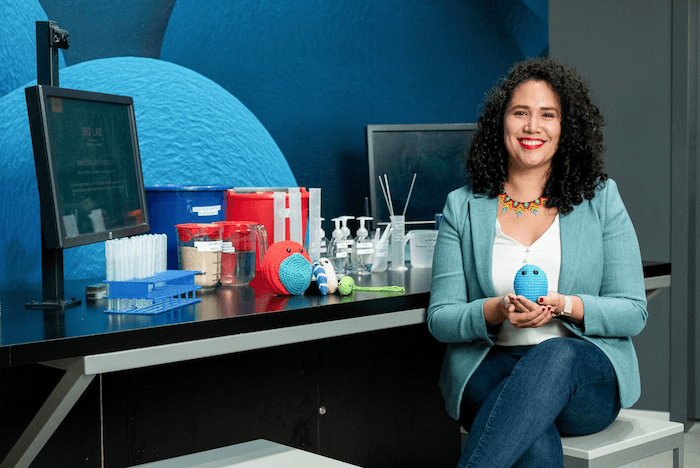

Ana Maria Porras, Ph.D., has crocheted nearly 100 science-related creations, most of them original designs. “There's no instructions on how to crochet a Covid spike protein, you know?” Photo courtesy of IF/THEN Collection.

On biomedical engineer Ana Maria Porras’ Instagram, microbes that are typically invisible — and often unloved — are reimagined as cuddly, cute and crocheted. Browsing her social media, you’ll find a fuzzy yellow version of the bacterium that causes citrus greening cozied up to some fresh limes, or the flowing flagella of the microalgae Dunaliella salina crafted in neon pink yarn. For Halloween, she crocheted a toothy likeness of the parasitic bacterium Vampirovibrio chlorellavorus. Now her renderings of micro-organisms have landed Porras, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the University of Florida’s Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering, a likeness of her own: a life-sized statue of herself in a Dallas park.

The statue stands among a field of 3-D printed women in science, technology, engineering and math in the #IfThenSheCan exhibit, designed to encourage girls to pursue STEM careers. In part because of her art outreach, Porras was selected as one of 125 AAAS IF/THEN ambassadors, which led to her inclusion in the exhibit. (UF grads Jennifer Adler, a conservation photographer, and Allison Fundis, an ocean explorer and executive, have statues as well.)

On Oct. 21, Porras will travel to Dallas to meet her likeness for the first time. UF News asked her about the trip, her crocheted creations and what brought her to UF.

What will it be like to see a life-size statue of yourself?

It's really strange to think that I’m in the largest collection of statues of women in the world. I think it's going to be a little overwhelming. The group is so diverse in so many ways — ethnicity, national origin, occupation. If I were a little girl walking through, I would see there are so many different things you can do as a scientist and as an engineer. That's really powerful.

Why crochet microbes?

Microbes aren’t inherently bad. I think it's nice to portray them also in a way that makes them look cute to take a little bit of stigma away and make people think about them in new ways. It also helps because I’m doing this work on social media and that's a very busy, overpopulated space. I tend to use really bright yarn, and that’s on purpose to catch people's attention. You attract them with cuteness and then you deliver a little bit of science.

I started to do #MicrobeMondays on my Instagram. About a month later, a cousin of mine in Colombia said she loved what I was doing, but she couldn't understand it. That made me realize that there was a lot less science communication and online public engagement in languages other than English, so I started a Spanish-language account where I do #MicroMartes.

What drew you to study microbes?

My PhD program was all about using tissue engineering to create models of disease in the lab. I used to study aortic valve calcification. I really liked what I was doing, but most of the applications have been problems that are particularly relevant to people who live in the global north, in North America and in Europe. I really wanted to have the opportunity to collaborate with people where I am from in Colombia and study things that are relevant to me. I was looking for a topic that would allow me to do more global health science. My postdoc work at Cornell looked at differences in the composition of the microbiome between different populations, then using a mouse model to understand how those differences impact susceptibility to infection.

How are you continuing that work at UF?

We build models of diseased tissue in the lab so that we can study how microbes interact with human tissue. Understanding better how our microbiome can control our health is one application. The other application is thinking about bad microbes, or pathogens, and understanding how microbes drive tropical infectious diseases.

Why did you choose UF?

I'm really interested in global everything: science, teaching, science communication, research. The International Center here on campus is so well equipped to support that, as well as UF being a leader in studying emerging infectious diseases. I'm also really drawn by the high proportion of Hispanic students that we have here compared to most of the schools I have been at since I finished my undergrad at UT-Austin, and also the same for staff and faculty. In the last month I've met more Latinx faculty here than I had in my previous two institutions in 10 years. The fact that I can speak Spanish in all aspects of my job — not all the time, but sometimes — I just feel very at home here.