Can song, murals and other art forms help us achieve better health?

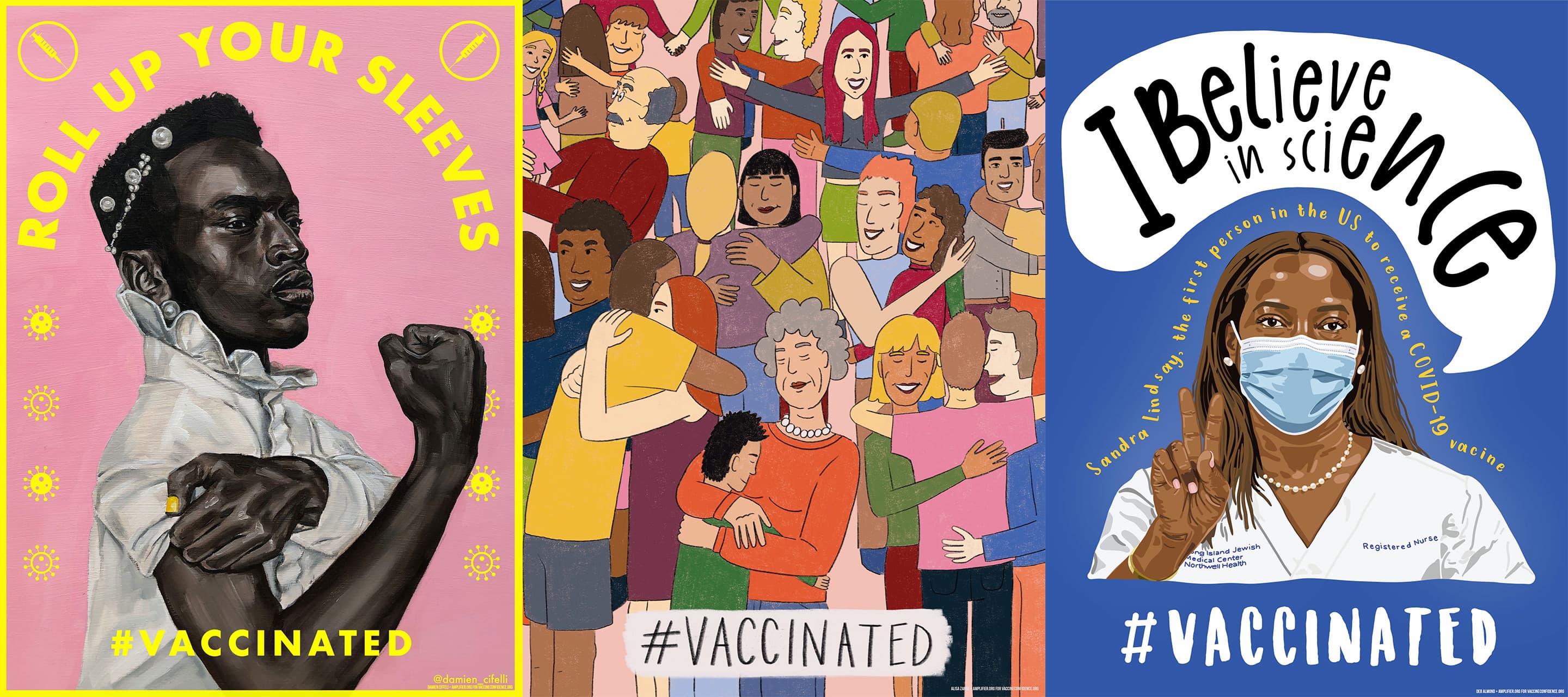

Roll Up Your Sleeves by Damien Cifelli, Vaccinated by Alisa Zangl, I Believe in Science by Deb Almond | Contribute to and download this and other free COVID-19 Vaccine related art at amplifier.org.

Welcome to From Florida, a podcast where you’ll learn how minds are connecting, great ideas are colliding and groundbreaking innovations become a reality because of the University of Florida.

As trusted influencers, artists and culture-bearers communicate information in ways that make it both understandable and memorable. That’s why the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention turned to Jill Sonke, director of the Center for Arts in Medicine at the University of Florida, for help crafting a plan to bring public health and arts and culture organizations together to empower vaccine confidence. In this episode of From Florida, host Nicci Brown spoke with Sonke about her work as senior advisor to the CDC’s Vaccine Confidence and Demand Team. Produced by Brooke Adams, Patricia Vernon and James L. Sullivan.

Transcript:

Nicci Brown: Welcome to From Florida, a podcast where you learn how minds are connecting, great ideas are colliding and groundbreaking innovations become a reality at the University of Florida. I'm your host, Nicci Brown.

Today, I am pleased to have with me, Jill Sonke, the director of the Center for Arts in Medicine. Jill is an affiliated faculty member in the School of Theatre and Dance, as well as the Center for African Studies, the STEM Translational Communication Center, the One Health Center and the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases.

And for the role that we're going to be talking about today, Jill is also currently the senior advisor to the CDC Vaccine Confidence and Demand Team, which is part of the CDC’s COVID-19 Task Force.

A warm welcome to you, Jill. We are so glad you could join us.

Jill Sonke: Thank you so much, Nicci. It's great to be here.

Nicci Brown: Let's start with a little background about you and the center. Where and when did your journey begin as an ally and advocate for the arts and medicine?

Jill Sonke: Well, it began when I came to Gainesville and started teaching as an adjunct faculty member in the School of Theatre and Dance. At the same time, the Arts in Medicine program was just beginning to bubble up at UF Health Shands Hospital. I had earlier in my life, when I was in high school, I was heading toward a career in medicine. I was volunteering in hospitals from the day I turned 14 and was eligible to do so. And I took a turn from that pathway when I began dancing at the age of 17 and then went full steam ahead to dance, had a career in New York City. Then when I came to the Gainesville and started teaching at the university and heard about this Arts in Medicine program, it just felt like the most extraordinary opportunity that I could be an artist in health care and really realize both of my dreams together. It was really incredible to be able to step into that new program and to become one of the first two artists-in- residence.

Nicci Brown: You say the new program, but the University of Florida has one of the oldest programs for Arts in Medicine. Can you tell us a little bit about the history of the program?

Jill Sonke: That's right. In 1992, when I got involved, the artist-in-residence program was just beginning. But in fact in the late 1980s, a group of caregivers at Shands began to come together to explore their understanding of the health benefits of the arts related to their own lives. This was Dr. John Graham-Pole and a number of other care providers who recognize that they were dealing with the stresses of their work, their burnout and anxiety by turning to poetry and painting and music. They've rather informally started offering what they called “Laughter Play Shops” for other care providers and eventually a community member, Dr. Mary Rockwood Lane, heard about this. Her husband was a clinician and she approached John and said, “If doing art is good for you, don't you think it might be good for your patients as well? I think we should create an artist-in-residence program.”

That was the beginning of the artist-in-residence program. Another wonderful thing about this history is at the same time, the College of Medicine had started its own program. Tina Mullen, who is the director of the UF Health Shands Arts in Medicine program today, at that time had been hired by the College of Medicine to bring the visual arts into the environment of care. It took about a year's time before those two initiatives found each other and became one program, the UF Health Shands Arts in Medicine program. So that program was established in 1990 and was among five programs that began around that time in the United States. Now, of course, that small landscape has developed into a very robust landscape where there are arts programs now at least half of hospitals in the United States.

Nicci Brown: Jill, what is it about the arts that makes it such a powerful tool to communicate about health?

Jill Sonke: That's a great question, Nicci. There are a number of things. On one level, it's about the artists themselves, artists and culture bearers, those who hold the cultural and creative practices in communities and in groups. Those folks tend to be trusted members of communities, they are people who listen, they are people who question, they're people who care innately about the well-being in their community, and they are people who take action and they rally people to action collectively as well.

The CDC thinks of artists and culture bearers as trusted messengers. They're people who facilitate really important dialogues in communities.

And then the arts themselves are so powerful. Like, they're fun. We want to come to them, more than we want to come to maybe a PSA or a billboard, just to compare with some other more traditional public health forms of messaging.

They also put ideas and information into very personal and cultural contexts. They make them really personally and culturally relevant for us and they can make information more understandable. They facilitate dialogue. We go to see a great film, we go to a concert and what do we say to one another after? What did you think? We just dive into talking about it because they're compelling in that way. And in those dialogues, we consider the difficult issues and vaccination can be a difficult issue, right? So, that the dialogue that's facilitated provides opportunities for people to consider their own values and decisions.

I do want to say, this is not about propaganda and about persuasion, though, we certainly want everyone to get vaccinated. I believe this is a really important moment for this, but I also believe that the arts are uniquely powerful in allowing people to make their own decisions and that's really important to me in this moment. They enable that kind of personal insight that facilitates personal decision-making. And in turn, through that dialogue, they can really drive collective action. Artists have been agents of social change throughout our human history and this moment is no exception.

Nicci Brown: You recently collaborated with the CDC on a project to boost public confidence in COVID-19 vaccinations, which, of course, has become such a large issue. How did that collaboration come about?

Jill Sonke: I actually love this story. When the CDC formed its vaccine task force, it brought together a group of incredible people from across its divisions and the majority of those people were public health professionals who had worked in other parts of the world on health communication campaigns. And they all recognized that in those contexts you would never launch a major health communication campaign without artists, without songs, without dances, without the visual arts. They decided, why not here? We need the arts, it's time for this to happen in the United States. This is the moment, in this critical moment, for us to bring artists and culture bearers in community to bear in addressing vaccine confidence.

Nicci Brown: Can you tell us a little more about the initiative and the projects that you actually led?

Jill Sonke: Sure. I was appointed at the beginning of June as a senior advisor to the Vaccine Confidence Team on the Vaccine Task Force, as you mentioned, with the assignment to create field guides as a part of a kind of a multimodal initiative that the CDC was launching. They had partnered with the Georgia Department of Public Health and with two arts organizations in Atlanta to mount a pilot, a demonstration project, to use the arts to partner with local artists, to bring vaccine information into communities. They had also made a plan to create a funding stream for arts organizations to be funded to do this work, to partner with artists and culture bearers across the country.

They knew that if they were to make funding available that there had to be guidance. They asked me to serve as co-author on two field guides. I developed, in partnership with the task force, one field guide focused on developing partnerships between public health departments and professionals and arts organizations and artists, and a second focused on developing creative campaigns and arts-based communication programs within those partnerships. Those two field guides were released about a month ago. So, the CDC foundation now has $2.1 million available for arts organizations to partner with public health departments to engage in vaccine confidence work. They plan on awarding about 30 grants of about $75,000 each.

Nicci Brown: What kind of evidence is there that art actually does influence well-being and health behavior?

Jill Sonke: There's evidence, Nicci, around the arts and health communication, including in the Ebola epidemic, incredible things happened. I did research with our team here at the University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine on what happened in the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, the way musicians stepped forward at the moment when the general public was very distrustful of health professionals and when, especially in Liberia, the idea that Ebola was a government conspiracy was widely held.

Musicians stepped in and started writing songs. There was the first song was written by two artists named D-12 and Shadow, and they just were frustrated with the situation. They just at home one night recorded a song called Ebola in Town, and within a week it was topping the charts and playing on the streets and in dance halls and on the radio. UNESCO and USAID and the World Health Organization took note. They came in and immediately started partnering with artists. The second song that was released was called Ebola is Real, written in partnership with public health professionals to counter that conspiracy theory.

There is a long history around the world of the arts being used in health communication and some very strong evidence that arts-based programs can, in comparison to more traditional public health methods, lead to more behavior change.

There also, as you asked Nicci, is a lot of evidence around their relationship between the arts and health and well-being. We established about a year and a half ago here at UF the EpiArts Lab, which is a National Endowment for the Arts research lab. It's a partnership with Dr. Daisy Fancourt at University College London. Daisy is really the leading researcher globally in this area. She's published over 100 studies now that look at associations between arts and cultural participation and health outcomes, and the findings are extremely compelling using longitudinal, large cohort data sets in which she can essentially simulate randomized clinical control trials.

She's found associations, for instance, between participating in arts and cultural activities just once a month or more leading to 48% less likelihood of the development of depression among people over the age of 50. Similarly, significant reductions in loneliness. Children who engage significantly in creativity are also about 50% like less likely to be maladjusted and the implications for lifelong health there are very, very significant.

She's also found significant reductions in age-related disability and chronic pain, and she's even replicated studies that were done in Scandinavian nations, beginning in the 1980s and now through her work in the UK, that show associations between arts participation and longevity. So people who engage more than just every few months or more and arts and cultural activity have a 31% lower risk of dying early than people who don't. And these studies are all really well controlled for things like socio-economics and education, geographic location.

Those social gradients do exist. we know, in arts participation, but they are not a factor in the relationship between the arts and health and well-being.

Our EpiArts Lab is now using Dr. Fancourt's statistical models, and seven longitudinal American data sets and we're doing studies to investigate the associations between the arts and an array of health outcomes in the United States, which is a very different context. And we're finding very similar and really compelling associations between arts participation and a number of age-related outcomes and child development. Most notably, one of our recent analyses showed a really exciting association between arts participation and reduced what's called delinquent behaviors, behaviors that can result in engagement with the juvenile justice system and behaviors that are often maladaptive. We're really excited about advancing that research here and broadening the understanding in the United States of the health benefits of arts participation.

Nicci Brown: Can we dig into that just a little bit further? How does the United States compared to other countries in enlisting the arts in major public health initiatives?

Jill Sonke: Well, frankly, we've been a little bit behind. Since 2010, I've been doing research in other parts of the world around how the arts are used in public health. I started that research in east Africa because I noticed in Uganda, the arts have been a primary means of health communication and health education since the 1950s. The government has invested in the arts and the Ministry of Health employs a lot of artists. In fact, when I'm in Uganda, I always laugh because artists will say, “Thank God, I'm an artist, I can always work because there are jobs in public health for artists,” which is really wonderful. It's just common sense. In one of the interviews I conducted with a senior member of the Ministry of Health, my first question was, “Why do you use the arts in public health?” He kind of furrowed his brow and looked at me like I was an idiot and said, “Well, you can't do public health without the arts. You can't just tell people health information, you have to engage them emotionally.”

He had a deep understanding of aesthetic experience, the idea that when we have aesthetic experiences, those moments that are different than other more mundane moments, we have them in art, we have them in nature, they're moments that mark themselves in our memory and in our lives, they are memorable, they have lingering effects. And when we engage people with health concepts in those kinds of moments, not only do people understand and remember information, but they engage in narratives and in dialogues that help them consider their own lives and values and help them make choices that they can really commit to.

And then when they tell, in fact, speaking of the evidence, Nicci, when they tell other people about those aesthetic experiences and the health issues that they're considering, those people are even more likely and quick to change their health behaviors. There's a very interesting social learning phenomena that contributes to the value of the arts in public health.

Back to your question, we've been a bit behind in the public health sector in the United States. In our culture, we have a very professionalized arts context, right? You're an artist, or you're not, you pay to go and see the arts. I mean, that's a gross generalization because there's also a lot of art and creativity that happens every day in our homes and in our communities, but in comparison to some other cultures, we do separate the arts from the fabric of our daily lives, more than other places do. I think that in our health care and in our public health context, the arts are sometimes considered soft, right? The soft stuff.

In fact, about four years ago, we became a partner with ArtPlace America. They asked us to lead their arts and public health work. Our work was focused around creating a field of arts in public health and America, changing that paradigm in the United States. I thought it was going to be big, hard work. I often say, I thought it was going to be like pushing a big boulder up a hill. In fact, it was like chasing a boulder down a hill because the readiness and the sort of tipping point around understanding was so available and public health professionals and agencies have really stepped into this space. We're seeing a lot of enhanced understanding, activity and partnership across the public health and arts and culture sectors in the United States right now. And educational programs and conferences and symposium, research publications, just a lot of exciting things happening that really mark the development of a field and a discipline.

Nicci Brown: It sounds like we’re going to be seeing an increase in these types of programs being used to communicate issues surrounding health.

Jill Sonke: I’m optimistic that that’s true, Nicci, and I'm also really hopeful that we'll see that happening soon on our campus. We've just developed a partnership between the Center for Arts in Medicine, the College of Public Health and Health Professions, the College of Journalism, and UF Health Communications to launch a campus-based, arts-based health communication campaign for vaccinations. So, more news to come on that soon.

Nicci Brown: It's heartening and exciting to hear about that kind of progress. If people are listening and they want to learn more about the field guides and the program repository, how can they do that?

Jill Sonke: You can go to the CDC’s Vaccinate with Confidence page. There's a landing page for the field guides there. There's a link to our repository there as well. We will be creating a field guide specific to funding these sorts of partnerships and projects next. And on the CDC Foundation’s website, you can find the request for proposals for the funding opportunities.

And then on the Center for Arts in Medicine’s web page, you can again find the field guides, our beautiful repository of arts for vaccine confidence programs around the country is accessible there as well as a webinar that we hosted a few weeks ago in partnership with the CDC and the National Endowment for the Arts. It's a one hour webinar which focuses on the Atlanta arts pilot, and a few other really beautiful programs – an organization called Hip Hop Public Health. It looks also at what the state of California is doing with their creative corps program. They've got $15 million dedicated to arts for vaccine confidence programs and beautiful work in San Francisco. So, lots of ways to find examples and to find those resources.

Nicci Brown: Thank you so much for spending some time with us today and thank you for your work. We very much appreciate it.

Jill Sonke: Wonderful to talk with you, Nicci. Thank you.

Nicci Brown: Listeners, thank you for joining us for another episode of From Florida, where we are sharing stories of faculty, researchers, students and administrators who are moving our state, our nation and our world forward through their innovations and discoveries. I'm your host, Nicci Brown and I hope you'll join me for our next story of innovation From Florida.