UF plant experiment flies on Virgin Galactic spaceship

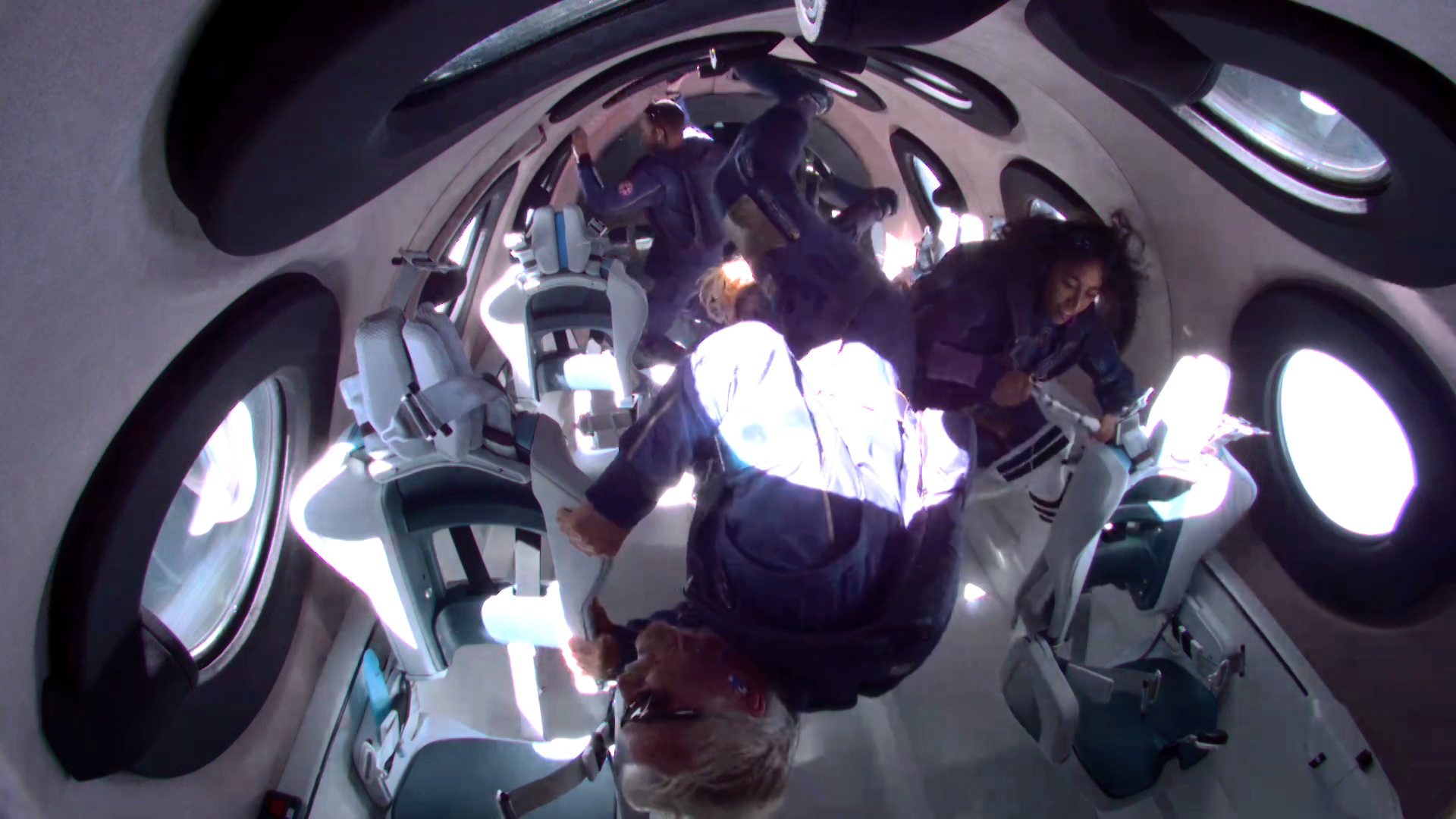

Astronaut Sirisha Bandla, right, can be seen activating a Kennedy Space Center Fixation Tube just as the Virgin Galactic spaceship reaches zero gravity.

While most of the attention during the July 11 launch of Virgin Galactic’s Unity spaceship was on billionaire company founder Richard Branson, University of Florida researchers Anna-Lisa Paul and Rob Ferl were focused on some other passengers – three small tubes of experimental plants.

The UF project, funded by NASA’s Flight Opportunities Program, was the only science experiment on the mission, meant to study the impact the transition to and from zero gravity has on gene expression in cells, and, more broadly, to develop protocols for “human-tended” suborbital flights.

“Although changes in gene expression are well characterized between orbital space (like the ISS) and on Earth, no science has yet been done to capture changes in gene expression during the transition to and from sustained microgravity,” said Paul. “This was a first-of-its-kind experiment that will reveal new insights into how terrestrial organisms perceive the transition into the novel environment of space.”

Paul and Ferl, both professors of horticultural sciences, have been working for more than two decades to understand plant gene expression in microgravity, but most of their experiments have been done by astronauts in space. As Paul puts it, on rocket launches the astronauts and their payloads are just “strapped in for the ride.”

But new platforms, like Virgin Galactic’s space plane, offer scientists the opportunity to have astronauts conduct research throughout the transition to and from space. To achieve this goal, the researchers had to develop systems that could be easily implemented during the brief periods of microgravity.

A custom-designed Kennedy Space Center Fixation Tube allows astronauts to easily “fix” the moment of gene expression so researchers can study what was happening at different stages of the flight to and from space.

Fortunately, Ferl and Paul have spent years fine-tuning experimental tubes called Kennedy Space Center Fixation Tubes, or KFTs, that quickly mix test materials (a model plant called Arabidopsis thaliana) and a fixative, while keeping both components isolated from the surrounding environment.

On the Virgin Galactic flight, astronaut Sirisha Bandla had three KFTs in a customized pouch attached to the leg of her flight suit. She activated one prior to reaching space, one as soon as the vehicle reached its maximum altitude and the crew became weightless, and one at the end of the period of weightlessness as the vehicle began its descent and gravity returned. On the ground, Paul and Ferl received telemetry from the flight that allowed them to activate identical control tubes at the same times as the flight tubes were activated.

“The successful use of KFTs enables a wide range of biological experiments in suborbital space, as any biology that can fit inside the KFTs can be sampled at any phases of flight chosen, in real time, by the scientist astronaut,” Ferl said.

Paul and Ferl retrieved the KFTs shortly after the spaceship landed and are bringing them back to their lab in Gainesville for further study.

“In the future, astronauts may go back and forth between Earth, the Moon and Mars and orbiting platforms like the International Space Station and the Gateway outpost orbiting the Moon,” Ferl says. “Understanding the changes that occur in cells during these missions will be important to maintaining their health.”