12 facts you didn’t know about seashells

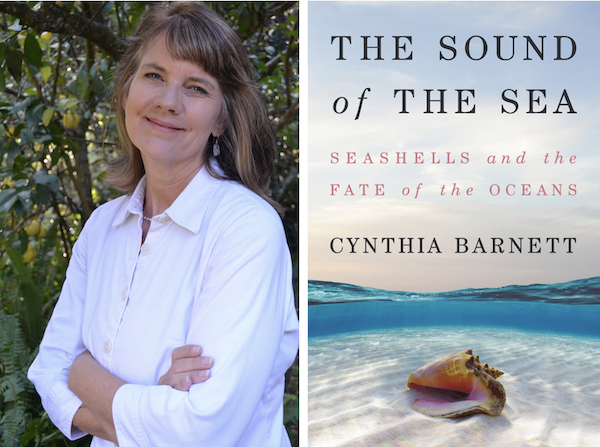

University of Florida environmental journalist in residence Cynthia Barnett structured her new book, “The Sound of the Sea: Seashells and the Fate of the Oceans,” around a dozen seashells that are both beloved by people and have an important story to tell about our world. In honor of those 12 shells and the mollusks that make them, here are 12 seashell facts from the book, which comes out July 6 from W.W. Norton & Co.

1) Humans have always picked up seashells for allure beyond food. Neanderthals are known to have collected empty shells along the Mediterranean Sea in what is now Spain. An ancient shell collection was even found in the rubble at Pompeii. Many of the shells in the collection, along with others found in Pompei, came from the nearby Mediterranean. But the collection also contained at least five other exotic species—including textile cones, gnawed cowries and giant clams— from far away: the Red Sea or the Indian Ocean.

2) A small cone shell, Conus ebraeus, is the earliest-known keepsake interred with a human. It was unearthed from the grave of an infant in a large, rocky cave in South Africa. It had been notched by hand, strung onto a pendant, and worn for many years before being placed with the Stone Age baby.

3) The first worldwide currency was not crypto, but a gleaming white seashell, the Money Cowrie. The small cowrie is a reef-dwelling algae eater in the genus Cypraea. Cypraea shares its Greek root with cryptocurrency: kryptos, meaning “hidden” or “secret.” The small shells were harvested en masse in the Maldives for a thousand years and used as money around the world. Money Cowries purchased an estimated third of the enslaved Africans forced to the Americas.

4) Humans have been brushing their teeth with seashells since at least the ancient Greeks, who crushed oyster shells into toothpaste as a cleaning abrasive, the same reason Crest adds calcium carbonate today.

5) The Calusa people of Florida left the most extensive shellworks known in the United States. These natural and cultural archives were almost entirely flattened for roads and farms. Mules hauling the shell-heaped carts across farm fields in the early twentieth century had to be fitted in special boots to protect the soft undersides of their hooves from the sharp shell spires and spines.

6) The origins of global oil giant Royal Dutch Shell can be traced to a small seashell curio shop in the East End of London in the 1830s. Seashell dealer Marcus Samuel Sr. conceived the shell-encrusted trinket boxes sold in seaside resorts to this day; they helped make the family’s fortune. Sixty years later, his son Marcus Samuel Jr. founded Shell Transport & Trading Co. to move oil through the Suez Canal. He named all the company’s first oil tankers—the earliest versions of the behemoths that ply the sea today—after seashells. The first was the Murex, also the name of a modern Shell tanker that carries liquefied natural gas.

7) America’s first shell book was written, illustrated and published in the failed utopian community of New Harmony, Indiana. American Conchology, published beginning in 1830, was written by Thomas Say and illustrated by his wife, Lucy Say, who is part of a rich history of women taxonomic experts denied professional opportunity in their time. They include Anna and Susanna Lister, teenaged girls who illustrated the first global encyclopedia of shells in the 17th century; Mary Elizabeth Lyell, a shell collector and taxonomy expert who aided her geologist husband Charles Lyell in the 19th century; and fossil pioneer Mary Anning, who also contributed to Lyell’s science without credit. Anning was long known mostly anonymously for the tongue twister attributed to her: She sells seashells by the seashore.

8) The only book of Edgar Allen Poe’s that sold well in his lifetime was a seashell guide he wrote for hire, The Conchologist’s First Book of 1845. Poe was accused of plagiarizing two other European seashell guides. But he is lauded by scientists for being one of the few scientific writers of his time to not only describe the shells, but give an anatomical account of the mollusks that build them.

9) The CIA considered assassinating Cuban President Fidel Castro with an exploding conch shell placed on a coral reef. In 1963, agents considered booby-trapping a “spectacular shell which would be submerged in an area where Castro often skin-dived,” according to John F. Kennedy assassination files declassified in 2017.

10) Edna St. Vincent Millay, the beloved American poet known for her romantic sonnets, was obsessed with seashells. Much has been written about the 1936 Sanibel Island, Florida, hotel fire that burned up her belongings including the original manuscript for her book Conversation at Midnight. Less well known is that she was searching for seashells at sunset when the fire broke out—hoping to find a coveted Junonia shell.

11) Indigenous Pacific people revered giant clams in cultural and spiritual traditions, but in the West, giant clams became synonymous with “killer clams.” The animal, the New York Times falsely reported in a 1930s travel story, “has caused the death of many natives and divers who have been caught by the foot and found themselves unable to wrench free.” The man-eating myth was so persistent that decades later, U.S. Navy diving manuals still advised frogmen how to free themselves if caught in the “vise-like” grip of a giant clam: by inserting a knife between the valves and severing the animal’s adductor muscle. Far from killing us, the world’s biggest shell-builders may help save us. Giant clams are living bioreactors, turning sunlight and algae into fuel. They use some of that energy to expel heat, which may be helping them adapt to the warming seas. Materials scientists are also studying the clams’ biology for applications in algal biofuels and cooling technologies—ways to expel heat from power plants, office buildings or car interiors without fossil fuels.

12) Cone snails, which make some of the world’s most-collected shells—like the Marbled Cone that Rembrandt etched from his personal collection—also make some of the world’s most powerful toxins, which they use to hunt their prey. The Geographer Cone’s venom is one of the deadliest toxins to humans. It was nicknamed the “cigarette cone,” to suggest someone stung by it would have just enough time to smoke a cigarette before dying. (Death actually takes a few hours.) But what kills in nature can also cure. Cone-snail toxin led to development of the pain drug Prialt, 1,000 times stronger than morphine without potential for addiction. Today, early research on the chemical changes happening in the oceans because of climate change indicates that acidifying waters could make the graceful cone snail hunters clumsy.