Lost and found: The tomb of the Sea Dragon, Brazil’s famous abolitionist

Through the heat of the Brazilian summer, Licinio Nunes de Miranda sweated in the cemetery.

For three years, the University of Florida doctoral student had been searching for the tomb of Francisco José do Nascimento, the revered Afro-Brazilian abolitionist known as the Sea Dragon. Nascimento’s heroism helped end slavery in Brazil, but despite the Sea Dragon’s renown, no one knew where to pay their respects. His tomb had been lost for more than a century.

While working on his dissertation on abolition in the northeastern state of Ceará, Miranda’s admiration for Nascimento grew. He marveled that a fisherman and sailor from a poor family organized the 1881 strike where Ceará dockworkers refused to board enslaved people onto ships to be sold throughout the country. Slavery, a cornerstone of Brazil’s economy for centuries, was outlawed in Ceará in 1884 and nationwide in 1888.

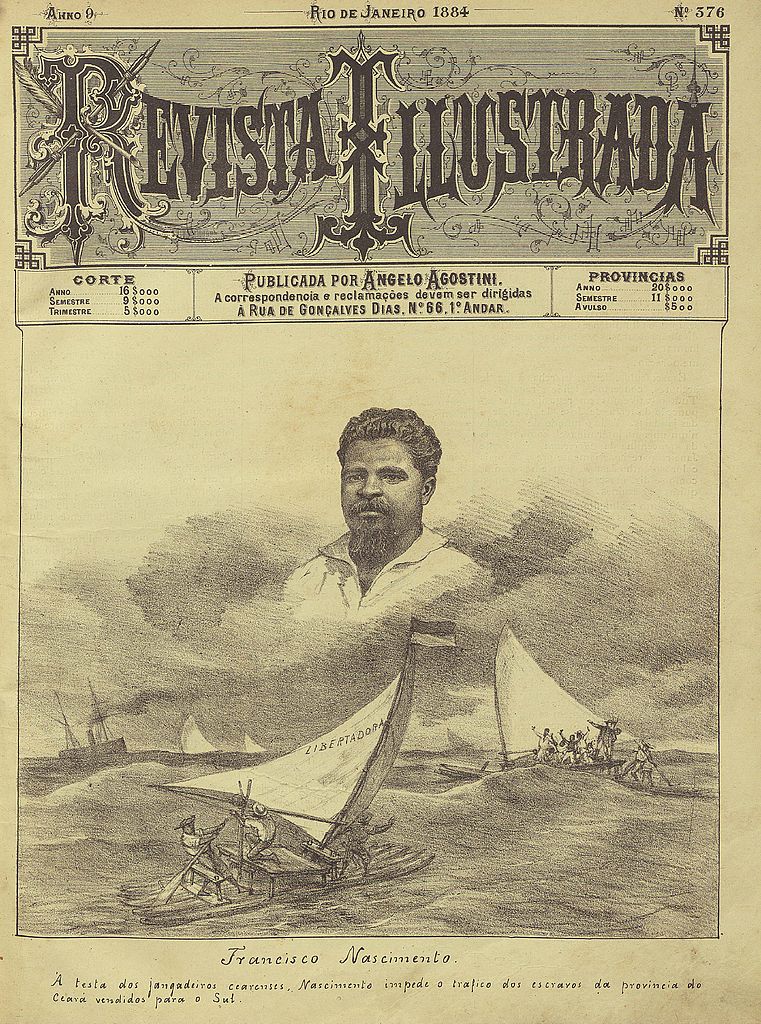

Francisco Nascimento, the Sea Dragon (Dragão do Mar), as seen in an 1884 illustration. Image courtesy of Biblioteca do Senado Federal.

It was the first major victory of Brazilians against slavery,” said Miranda, who grew up in Brazil and studies history at UF. “For someone from his background to have led that strike means a lot. It could have cost far more to him than if he had belonged to the elite."

Miranda became determined to find Nascimento’s grave, visiting archives for clues and searching the labyrinthine São João Batista cemetery in Ceará’s capital, Fortaleza.

Miranda felt certain São João Batista was the right place: It was the capital’s only cemetery when Nacimento died there in 1914. Beginning in 2017, Miranda spent day after day exploring the necropolis, systematically scrutinizing the ornate statues and sepulchers of its 12,500 above-ground tombs. Day after day, he found nothing. Then on July 24, 2020, he spotted a three-tiered monument covered in mold, the cross on top broken, its stone crumbling.

“DESCANÇO ETERNO do MAJOR FRANCISCO JOSE do NASCIMENTO.”

The eternal resting place of the Sea Dragon.

“It was very hot. I was sweating, but I was so happy, I didn't care,” said Miranda, who took a selfie at the scene.

University of Florida student Licinio Miranda on the day he located the tomb of the Sea Dragon, July 24, 2020. “More than me, of course, he earned it," Miranda said. "He deserves to be remembered.”

Since then, the tomb has been cleaned and restored, its rediscovery celebrated in news articles and events. Miranda, who had since returned to Gainesville, couldn’t go back to Brazil for the ceremonies because of the pandemic. But he’s gratified to see Nascimento’s legacy preserved, not just a footnote to history but as a reminder that in Brazil, as in the United States, racial inequities persist.

“We're still learning how to overcome those problems,” he said. “People can learn about tolerance, freedom and equality from these historical figures who did so much even though they had so little.”

Miranda is continuing his work revealing the untold stories of Ceará’s abolitionists, supported by UF’s Research Abroad for Doctoral students program. He hopes other students realize that their research can have results beyond academia.

“Current times have been so hard for everyone that I felt that we needed and deserved good news, especially concerning a man who had overcome hardships in times just as difficult as ours — and all for the sake of the common good,” he said. “If he did it, so can we.”