Women are underrepresented in science coverage. Two UF scientists share insight on how to have your voice heard.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, University of Florida epidemiologist Natalie Dean has lent her expertise to national and international news coverage countless times. But she continues to see women scientists underrepresented in the media, so she tweeted an appeal to female colleagues.

“I would really encourage women in our field to talk to the media more if you are able, even if it makes you feel uncomfortable,” she wrote. “Your insights are valuable.”

We asked Dean and fellow UF professor Michelle Cardel to share what they’ve learned along the way that could be helpful to those interested in diversifying conversations in the news and on social media.

Both Cardel, who studies obesity and health disparities and has a doctorate in nutrition sciences, and Dean, who studies infectious disease and has a doctorate in biostatistics, found themselves unexpectedly thrust into the media spotlight. For Cardel, an assistant professor in the UF College of Medicine’s Department of Health Outcomes & Biomedical Informatics, her foray into science communication began as a post-doctoral researcher, when her mentor asked her to fill in for him on a live television interview. She was terrified, but afterward, the producers asked her to come back, and she wound up hosting a weekly live segment. She continues to demystify nutrition and fight misinformation for her social media followers on Facebook and Twitter.

For Dean, an assistant professor in the department of biostatistics in the College of Public Health and Health Professions and the College of Medicine, expertise that was once fairly niche — studying emerging infectious diseases — moved into the public eye with the coronavirus pandemic. In a matter of months, her Twitter audience went from 200 to 36,000 and counting, gaining thousands of followers each week.

Cardel and Dean offered these tips to help women and other underrepresented scientists have their voices heard.

Be proactive

“My suggestion to all people, but particularly women, would be to seek out opportunities to get training and practice in science communication and to seek out media opportunities,” Cardel said. “Don't be scared to reach out to a journalist, or to your media communications people at your university and say, ‘Hey, this is something I'm interested in. This is my expertise. Let me know if there's ever a chance for me to do something.’”

Be visible

Dean credits her Twitter presence as part of her rise to prominence as an interpreter of her field in the media. On the platform, she offers her insights and reactions to new research. She also creates Twitter tutorials on infectious disease to help people understand the news, which have spurred requests from reporters to include the information in their stories. While the timeliness of her expertise drove the rapid growth of her audience, a steady stream of good content can help scientists build visibility over time.

“Twitter is quite democratizing in that way,” she said.

Be prepared

When Dean began to get interview requests from high-profile outlets like CNN, “I was extraordinarily nervous. One of the first people I called up was Michelle.”

Cardel’s advice: A few minutes of live TV can take hours of preparation. Hundreds of interviews later, Dean says, “I still get nervous, but I try to come in prepared with a particular set of points I want to make. I also make sure that I'm not using a lot of technical jargon.”

It's OK to ask reporters to provide their questions beforehand, or at least a rough idea of the topics they plan to cover. Just know that the questions might change, so it’s important to be nimble, Dean says.

Be selective

Once requests for interviews start coming in, how can you keep them from becoming too time-consuming?

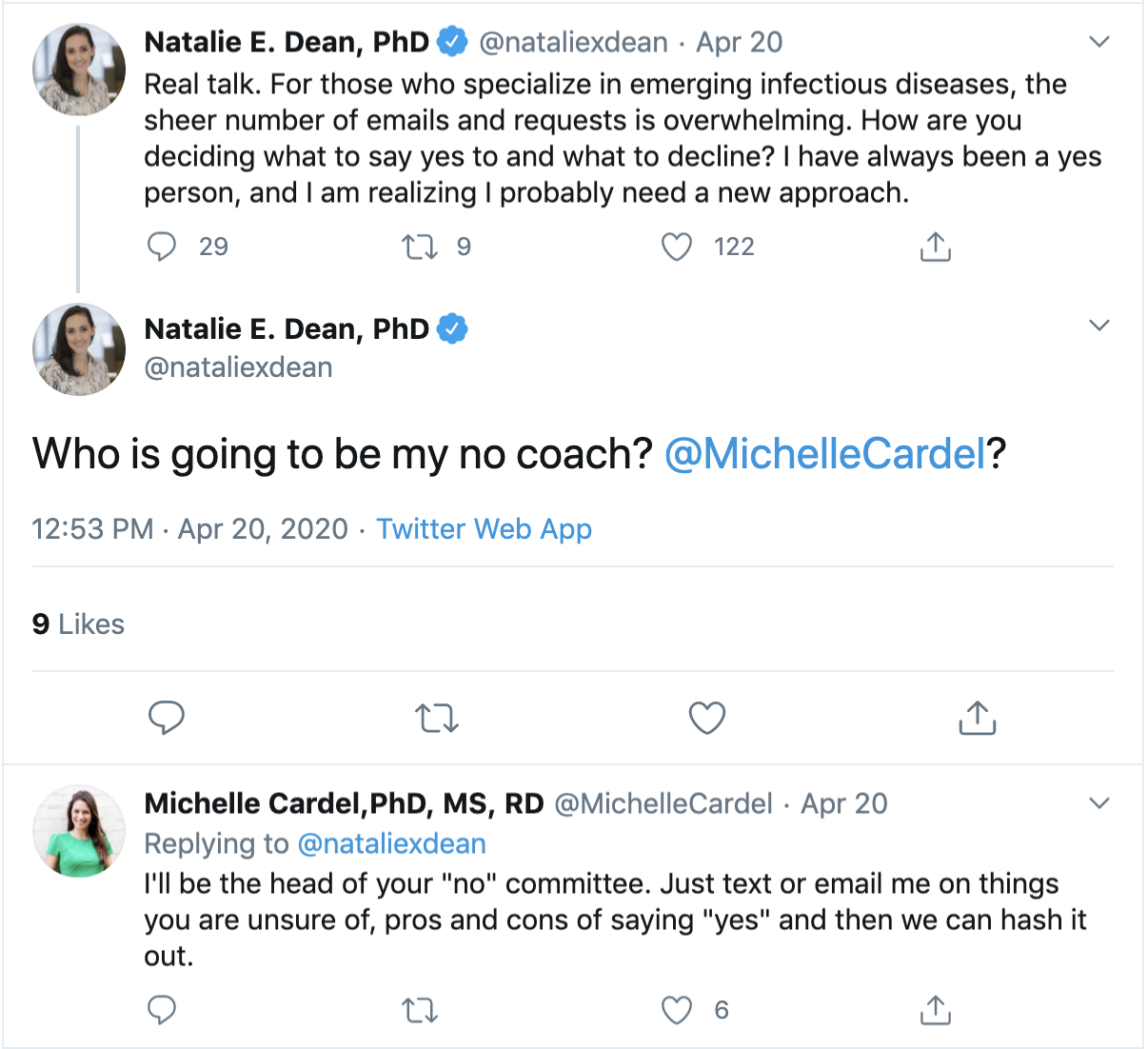

“At first I was really reluctant to say no to anything,” said Dean, who recently wrapped up a series of weekly radio interviews on BBC World Service. “Lately it's gotten to a point where it's become a bit overwhelming, so I'm trying to figure out ways to triage a bit and delegate to folks that I know can do a good job handling things, amplifying people's voices who might not otherwise be heard from.”

Requests that involve basic explanations of her field and don’t draw on her specific expertise might get passed along to a graduate student or postdoc who can provide the same information and also gain experience talking to the media.

Also helpful: putting limits on how much you engage with antagonists on social media, Cardel and Dean say.

“If somebody is trying to have scientific discourse and pointing out a flaw in my research method or in my communication of a scientific finding, I really appreciate that. I think that that's essential,” Cardel said.

“But if people are just in bad faith and they're being mean, ignore that,” Dean said.

The key, both scientists say, is to recognize that your voice is needed.

“I think that we are really enriched by hearing a diversity of voices,” Cardel said. “When we have women and people of color and people of a diversity of stages in their career, you really can get a more comprehensive picture on any topic, because people are coming from their different lived experiences. It's so important that the narrative reflects all people — not just a certain sector of the population that tends to get highlighted the most in the media.”