William Logan is an Alumni Professor and Distinguished Teaching Scholar in the University of Florida department of English. The author of 10 books of poems and six books of criticism, he is a regular critic of poetry for the New York Times Book Review. Professor Logan was the speaker for UF’s spring doctoral commencement ceremony on April 28, 2016. Below is his speech in its entirety.

My address this evening is titled “The Groves of Academe.” The phrase refers, as many of you know, to the olive grove, outside the walls of Athens, where Plato taught, and by descent to wherever the learnèd gather—the groves of academe. It sounds like a trendy Manhattan bar. When you leave the groves, where will you go? As Americans might say, you’ll hightail it out of the swamps, perhaps to the fields beyond, perhaps to other groves, where you too will talk, and teach. I’m not, by nature, an academic—indeed, apart from being a poet, and a growly sort of critic, I don’t know how Linnaeus or Darwin would classify me. Perhaps as a portmanteau creature, part this, part that.

My argument this evening—and commencement speeches are always arguments of one sort or another—is that you should try to be not merely one thing, but a multitude, sometimes in concert, sometimes at odds. As a parting gift—the big kiss-off, as they say in detective novels—let me offer some of the stray wisdom that has come my way over the past forty years. As Newton was said to have said, long after his discovery of calculus and the law of gravity, “I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.” Or, as I might say, in a long life even a stray dog will occasionally pick up a stick.

I stand before you as a teacher, in a cracked and cranky way, a teacher created by teachers. In 1972, when I wore little but Levis, tie-dyed T-shirts, and something called Earth Shoes, when I was protesting a war and upset even at peace, I had the overpoweringly vague desire to be a poet. Unfortunately, I’d already taken too many poetry workshops run by gentle, cigarillo-smoking, beret-wearing poetic types who could have hit me with a claw hammer without teaching me a thing. Fortunately, in my last semester I had two radically different professors who in a few weeks invented me.

The first was Richard Howard, who had already won a Pulitzer Prize in poetry. He taught me that imagination is compelled by restriction. He gave us various infuriating, torturous assignments. After I finished the first, I realized I’d been going about poetry the wrong way. I’d thought—like the poet Sir Philip Sidney—that you looked into your heart and wrote. Howard taught me that the imagination reacts when bound and gagged. Poetry turned out to be problem solving, and problem solving—having, until seventeen, been a calc and chem geek—I knew how to do.

The second teacher—he was a novelist—showed how character is formed in the tensions of language, how plot is a calculus of discovered necessities. As a student he’d been a darling of the Yale English Department, and at twenty-six he was hanging around Yale teaching small seminars for a pittance. Like Richard Howard, he taught by talking, talking, and talking, a skill I’ve never quite learned. He was at work on a never-to-be finished trilogy of novels; but his great talent as a writer—apart from a genius for analysis—was for dialogue. His name was David Milch, and later he created NYPD Blue and Deadwood.

Having teachers, I became a teacher. Twenty-five years ago, one of my graduate students buttonholed me before our final class and with some excitement confided that he’d had a dream in which I explained the Seven Last Things, what poets needed to know before they went out into the world. I took that as a challenge, and every year or two I find seven new last things with which to bedevil or entertain my students. I’m fond of minor traditions that give minor order to the world. I won’t claim that these seven snippets of wisdom will be a compass when you’re lost in a trackless waste, or your North Star when you’re drifting through the middle latitudes of the Pacific. Perhaps they’ll bear contemplation only when you arrive at your North Pole, the North Star directly above and no help at all. There, whatever direction you choose will be South.

Here are the Seven Last Things for 2016:

(1) Language

I said “hightail it” at the outset. “Hightail” is a good American verb, referring to a deer in flight. It’s not all that old—it goes back only to Teddy Roosevelt’s day. “Language,” said Emerson, “is fossil poetry.” He meant that many of our words derive from metaphor. When we say we’re “hogtied,” the metaphor is plain—you hogtie something by binding all four feet. Indeed, most of our language has a long history, words and phrases we use carelessly or by the way. When we say that someone is “on the wagon,” what do we mean? You have to go back to the first uses in the nineteenth century to realize the phrase has lost something. Originally it was “on the water wagon”—we still use it to mean someone no longer drinking the hard stuff. What was a water wagon? It sprinkled the dirt streets to lay the dust, as they used to say.

The language of wagons permeates modern English. Early automobiles were built by wagonmakers like Studebaker, which manufactured cars into the 1960s. Where is the speedometer located? On the dashboard, the front board of a wagon, the board that kept mud from splashing the driver. What do we call it when someone follows us too closely? Tailgating. The tail gate was the hinged board at the rear of the wagon. Hence—I hear you thinking—having a picnic on the tail gate of a car, perhaps a station wagon. Station wagon? The horse-drawn wagon that took freight and passengers from the train station. And of course we still measure our cars in horse power. Language is fossil poetry, and life is fossil language. We’re the sum of all we have said, and all we didn’t say. When you speak, use your words as carefully as a chemist titrating sulphuric acid.

(2) Pencils

Our thoughts are like words drawn in sand as the tide roars in. The best ideas may flit like mayflies across the imagination. The odd network of association and beleaguered memory that causes us to think something new may minutes later be entirely forgotten, along with that pointed insight, that deft poetic phrase. A surveyor once had to carry his theodolite and dumpy level, his Philadelphia rod and Jacob’s staff. George Washington’s kind of surveying is now digital, but a surveyor of the mental world still needs a pencil.

Remember that the German chemist Friedrich Kekulé [KAAK-oo-laY], after years of studying benzene, saw in a daydream a snake seizing its own tail, and realized the chemical structure that had eluded him was simply a ring. Elias Howe, trying to build a better sewing machine, dreamed that warriors were attacking him with spears, each weapon with a hole in the spearhead. Until then, sewing machine needles had their eyes at the tail, not the tip. Visual ideas are hard to forget; but ideas cast in language, those we need to write down. Wherever you go, whatever you do, don’t forget your pencil and your scrap of paper. Why not use a smart phone? One, history. Pencils are legacy tech, more than four hundred years old. Two, they never run out of power, just out of lead. Why “lead” pencils, by the way? Because graphite was originally thought a kind of lead.

Don’t be too fond of your digital devices, like the young man who tried to drive me across Lubbock, Texas, and took a long hour, because highway underpasses were blocked off and his GPS was confused, though the voice of Arnold Schwarzenegger kept rising from the dash, warning him, “Go back, go back!” I made up the last part.

(3) Misfortune

Some years ago, a man I knew, a partner at a law firm, was fired. He didn’t like working for that firm; but there were bills to pay, children to raise, and later alimony. When he was fired, he cast about for something new and in two weeks had his dream job, working as in-house counsel for a small pharmaceutical company. That would not have been my dream, but it was his; and he’d never have fulfilled it if not for the misfortune of being fired. Ten years later, when that job ended, he got another dream job. Just as he was getting used to a desk the size of the Titanic, he heard on the morning news that his new company was caught in the middle of an environmental disaster. Sometimes the hard proves easy, and the easy, hard. You can’t take out insurance against slings and arrows—sometimes you just have to leap. And hope.

(4) Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Burke, known as “31-Knot” Burke, was a naval officer during World War II, commanding groups of destroyers in the Pacific. He believed that the worst sin of the Navy early in the war was . . . hesitation, and that at the Battle of Blackett Strait he’d made a mistake not ordering his ship to fire when the radar operator first made contact with the enemy. His standing orders to his destroyers afterward were to attack the enemy without seeking permission. “The difference between a good officer and a poor one,” Burke later said, “is about ten seconds.” The Navy’s modern class of destroyers is named after him. The frontiersman Davy Crockett would have understood. His motto was “Be sure you’re right. Then go ahead.”

(5) One Liners

You want to be, not the person who has to say two thousand words to get to the point, but the person who can condense to a sentence or an equation what has never been thought before. There’s an old anecdote about Sidney Morganbesser, a philosopher who taught at Columbia. The famous Oxford philosopher J. L. Austin had come to New York to give a paper about the structure of language. Everyone knows there are positives and negatives, he declared, and that in English a double negative was a positive. In no language, however, was a double positive a negative. There was silence, then from the back of the hall Morganbesser’s voice rang out: “Yeah, yeah."

(6) Education

The university, you may be surprised to hear, is not the place where you get an education—it’s where you learn to educate yourself. The fiction is that you enter the great maw of American schools when you’re six or so, and you exit twelve, or sixteen, or twenty-two years later with whatever you need to know as an adult. As my father used to say, “Hardy-har-har.” All sorts of things, like taking out a mortgage or changing your oil, aren’t covered in college. What you’re really being taught is how to read and how to think, so that faced with any problem, from disabling your track pad to building a kite, you’re able to teach yourself . . . sometimes with the help of YouTube.

A true reader, a true seeker, doesn’t need the university afterward. The university may prepare you, may save you time; but then you go out and . . . and learn. And the main way to learn deeply, freshly, radically, is to read. Fresh ideas come far afield—applying the unknown known to the known unknown. What should I read, you say? Follow your instincts, letting each book lead you to the next—no matter how far. I read while I’m shaving—I get through fifty or sixty poetry books a year that way. I read while walking.

(7) Last Words

Those are the words we utter when death is at the door. Some deathbed speeches are probably composed in advance—worse, most are apocryphal. My advice is to live your lives, not as if you’ll never have to say last words (wouldn’t that be nice?), but so that when you come to that hour you’ll have already said, to those you love and those you don’t, all that needed to be said. Still, if you want to say something memorable, take these examples—with a grain of salt.

Kit Carson, the brutal frontiersman and scout: “I just wish I had time for one more bowl of chili.” The philosopher Voltaire, when a priest asked him to renounce Satan: “My good man, this isn’t the time to make enemies.” Drummer Buddy Rich, as he was prepped for the surgery he did not survive. The nurse asked, “Is there anything you can’t take?” Rich replied, “Yeah, country music.”

Oscar Wilde, dying in a horribly over-decorated hotel room: “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or the other of us has to go.” Those weren’t his last words—only his last interesting words. It would be lovely if, as is sometimes reported, Emily Dickinson’s last words were “I must go in. The fog is rising”—but those misquote a letter she wrote two years before she died. Let me leave you with the epitaph on a gravestone in Kansas, seen by the writer William Least Heat-Moon, “Thanks for stopping by. See you later.”

Now, before I hightail it, before I release you back to your lives, to your parents, your friends, your lovers, and to the strangers you will one day meet—to you who are philosophers, historians, mathematicians, growlers, buccaneers: whatever you choose to do, don’t waste the hours before you. Live passionately, live as if no one had lived that life before—because no one has. “Be sure you’re right. Then go ahead.” Davy Crockett also said, “You can all go to hell. I’ll go to Texas.” Doctors, congratulations.

Download William Logan's speech

Campus Life

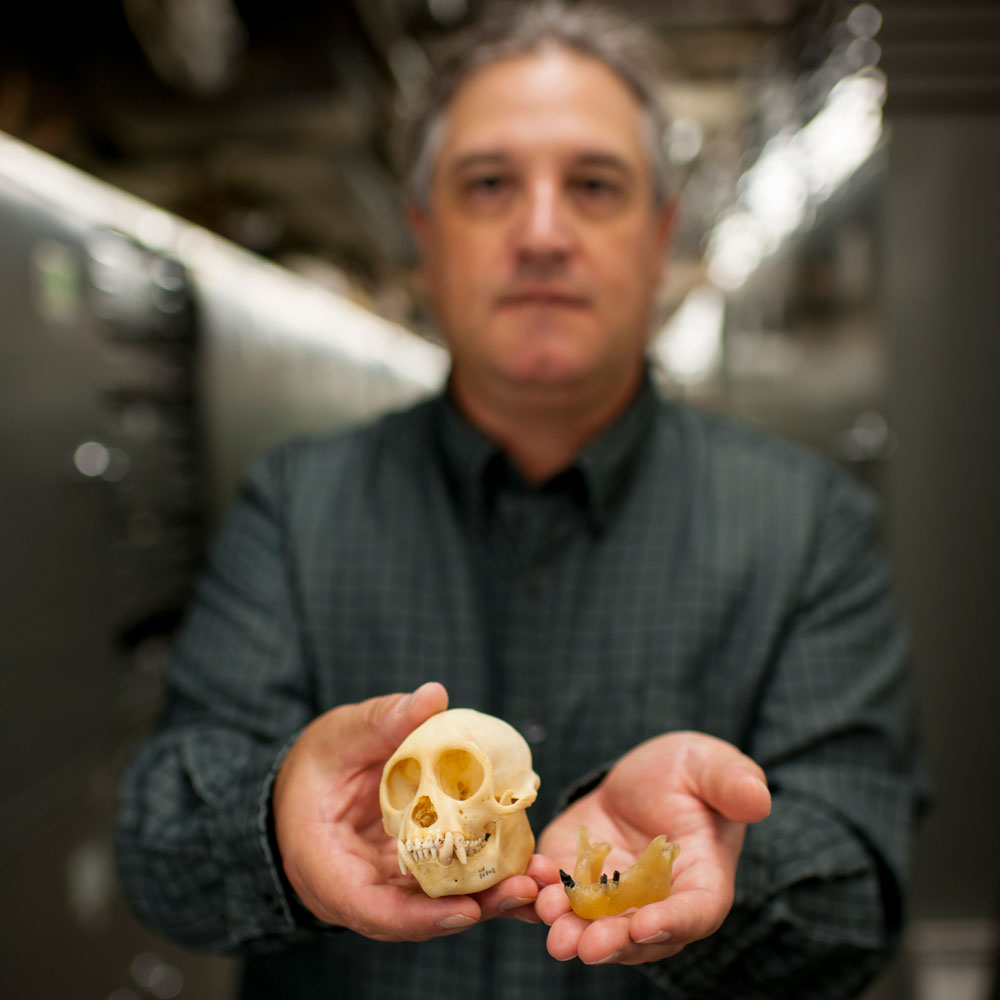

Nathan Jud shows a cycad with damage from leaf-mining flies.

Nathan Jud shows a cycad with damage from leaf-mining flies.